The highs and lows of restoring a remnant wetland on Aotea Great Barrier Island. By John Ogden and Lotte McIntyre

Aotea Great Barrier Island is home to significant natural wetlands that retain much natural character, including the 320ha Kaitoke swamp and the 400ha Whangapoua wetland, mangroves, and estuarine system. Together, they constitute the biggest wetlands in the Auckland region.

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Summer 2022 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

This is a dynamic system, potentially susceptible to climate change-driven storm events and sea-level rise.

Since January 2021, a small group of conservation volunteers – mainly Oruawharo Bay residents – have been restoring a rear dune wetland at Oruawharo Medlands Beach on the southeast coast of Aotea.

Oruawharo Bay used to have an extensive wetland, but most of it was drained and converted to pasture last century. A small remnant of this former swamp area, trapped between the main road (the only road!) and homes dotted among the dunes, is the subject of this article.

Since the Oruawharo wetland was drained many years ago, dry years have allowed an influx of rats and weeds, and during wet years feral pigs invade to dig up raupō rhizomes (and everything else).

Aotea has the largest area of possum-free forest in the country and no mustelids, hedgehogs, deer, or goats. Unfortunately, feral pigs, feral cats, ship rats, and kiore are still causing massive amounts of ecological damage.

In late 2018, a small group of residents formed the Oruawharo Medlands Ecovision Group with the goal of restoring the ecological health and biodiversity of their bay. At this point, wetland protection and restoration on the island was almost non-existent.

We applied for funding so we could launch an ambitious wetland restoration programme to remove exotic invasive plants, trap predators, and restore habitat for rare birds, including matuku hūrepo Australasian bittern and pāteke brown teal, reptiles, and invertebrates. Our work is supported financially by Great Barrier Local Board and the Department of Conservation.

DOC provided funding for rat and feral cat control, pampas (Cortaderia selloana) control, and judicious planting. Auckland Council, always supportive, has the wetland listed as a Biodiversity Focus Site Area. Upstream landowners Aotea Brewing started riparian planting, and the Aotea Great Barrier Environmental Trust offered administrative support.

We sample the water quality quarterly using the Waicare platform. The Oruawharo wetland changes from saline estuary at one end to mostly fresh water at the other. But the overlap between these influences varies almost weekly.

A layer of volcanic ash at about 50cm deep in the sediment indicates most of the area was a shallow saline lagoon before 1300AD. Soon after, local fires and increased erosion caused rapid infilling and the spread of raupō.

The Oruawharo wetland. Image Lotte McIntyre

As the surface dried, mānuka invaded, creating a greater fire risk. Human-engineered drainage reduced the area to its present extent and lowered the surface. The dry organic matter oxidised and shrank, rendering it more susceptible to flooding. Sea-level rise may yet recreate the former lagoon!

These changes and variation over time emphasise the importance of having a clear goal for our restoration. What exactly are we aiming to restore?

In our first vegetation survey, we found raupō and jointed twig rush (Baumea articulata) form most of the vegetation, but alien weeds accounted for a whopping 80% of the 30 plant species.

We know certain plants, now abundant, were not present in the system before European times, in particular kikuyu (Pennisetum clandestinum), pampas, and Mexican devil (Ageratina adenophora). Our first, and perhaps hardest, restoration goal is to remove these alien plants and replace them with native species that were formerly present.

The Oruawharo Medlands Ecovision project area. The blue line shows the wetland boundary. Image supplied

KEY: red dots = traps; yellow dots = tracking tunnels; purple dots = bird count location 2019 - 2021.

We have reduced huge clumps of pampas by judicious use of herbicides and hand-operated weed eaters that can cut down the clumps. These areas are being planted with mānuka, harakeke flax, tī kōuka cabbage trees, and kahikatea, which will hopefully prevent much pampas regrowth or re-invasion. Harekeke will be used to create dams to retain water in summer.

Our aim is to restore a mix of ecosystems each inhabited by their characteristic birds. We plant raupō around shallow pools, twig rush in older areas with deeper sediments, and mānuka on drier areas converting to more varied forest with time. Kahikatea will replace Casuarina she-oak, creating shady habitat for pāteke on the old creek.

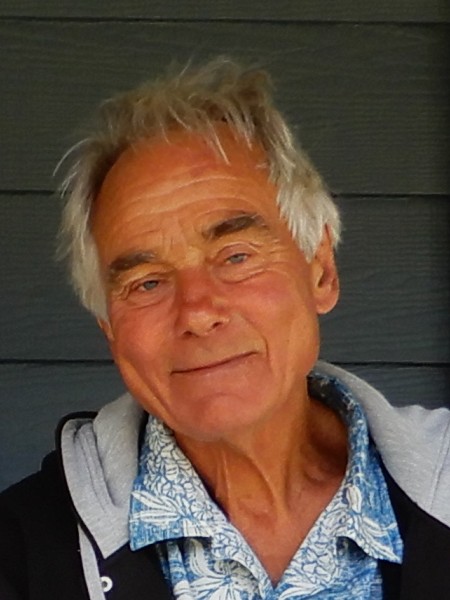

John Ogden, retired associate professor of Ecology at the University of Auckland. he has been involved in wetland ecology for 50 years. Image supplied

Native vegetation cover will create a better habitat for other birds, including pārera grey duck in drains and ponds, bittern in the raupō, pūweto spotless crake in the twig rush, matātā fernbird in the mānuka and Gleichenia fernland, and shags coming in from the coast to catch eels and other native fish.

Nearly 500 plants from the two nurseries on the island have been planted this year. Most of these went into the raised ground alongside the drains, helping shade out the kikuyu. Around the ponds, we will plant harakeke, cabbage trees, oioi, and Carex secta. Where mānuka is already established, we will try mahoe, red matipo, kawakawa, and karamu.

We have a small group of dedicated volunteers to get all this work done. It is a big restoration project on an island with a small available workforce. It is the same handful of people showing up to clear grapevines and pampas seedlings – but what a difference they have already made in two years!

Lotte McIntyre is the project coordinator, an enthusiastic wetland novice who also runs the local Aotea Trap Library.

This important restoration project presents an opportunity to show the public what lives and breathes in this wetland – flora as well as fauna. Knowing that Oruawharo Medlands is a tiny component in the wider wetland web connecting the coastal areas of Aotea – in both space and time – is both sobering and exhilarating.

Making the wetland accessible with pathways, boardwalks, and bridges would be an amazing way for locals and visitors alike to experience a beautiful ecosystem and biodiversity gradient.

Our original vision for the wetland included the installation of picnic benches, informative signs, areas to contemplate and carry out a spot of bird watching, and a relaxing meandering walking track to view the scenery.

But, to date, no funding has been available from the local council or DOC for this sort of infrastructure, so these plans have been put on the backburner for now, though not forgotten.

Our volunteers are brimming with enthusiasm to see the full project, including new visitor amenities, being accepted by the authorities and supported by the local and regional community.

Matuku-hūrepo bittern. Image Matthew Herring

What's in the wetland?

Matuku hūrepu bittern are under threat from habitat loss throughout New Zealand, and the presence of one, sometimes two, bitterns in our wetland is reason alone for protection.

Other birds that visit include matuku moana white-faced herons, kawua tūī little black shag, spur-winged plover, and pūkeko. Mātātā fernbirds have been seen, and spotless crake are present in the Kaitoke wetland, so we are hopeful that soon they will return to Oruawharo.

We have little idea what lives in the creeks, except galaxiids, common bullies, and eels, and southern bell frogs in the ponds. There is almost no knowledge of the insect life except for dragonflies and a few moths, but welcome swallows are consistently present, so there must be plenty flying about.

There are moko skinks in the wetland and niho taniwha chevron skinks a little further up the creek. Although Aotea is supposed to be a stronghold for pāteke, their numbers are declining, so creating forest wetlands free of predators where these brown teal can successfully breed is vital for their survival as a species.

We plan to plant a narrow zone of salt marsh ribbonwood (Plagianthus divaricatus) along the saline creek section for the pāteke.

Reversing wetland loss

Wetlands are referred to as nature’s kidneys because of their natural filtration system and their capacity to mitigate flooding and erosion. Coastal wetlands are a vital link between land and sea, shaped by factors such as the underlying geology, soil type, and climate as well as salinity, current velocity, and the permanence or transience of the water.

In the Auckland region, 97% of wetlands have been destroyed because of drainage and development, so protecting and restoring what we have left is widely seen as a priority today – not only in the Auckland region but nationwide.

Wetlands are home to many native species, both plant and animal, some of which are now endangered because of this huge loss of habitat. These areas also act as nurseries for native fish, as well as many birds and plants.

This article was inspired by Forest & Bird’s Every Wetland Counts campaign.

To download a copy, go to www.forestandbird.org.nz/everywetlandcounts.