During the Sanderson years (1923–1945), the Society focused on a range of conservation issues, including wild bird poaching, gazetting new nature sanctuaries, stronger wildlife laws, forest protection, and the control of “noxious animals”.

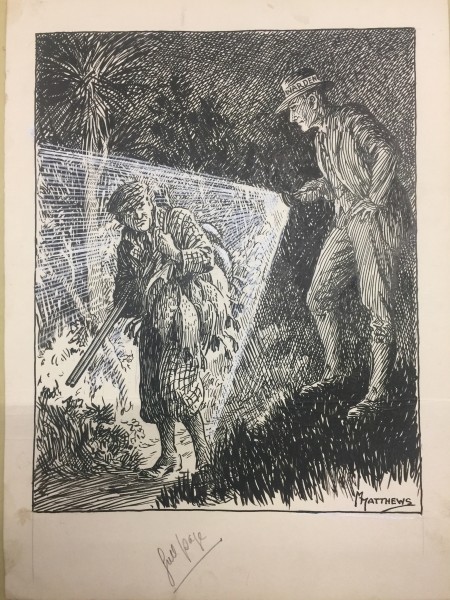

“The light he abhors but rarely meets” Anti-poaching cartoon commissioned by Forest & Bird, published May 1938. Image Marmaduke Matthews

In 1925, Sanderson was warned by an eminent New Zealander living in the United States that an expedition was being formed to collect vast numbers of birds from Aotearoa.

His informant told him the view at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard was that New Zealand’s indigenous birds were “doomed” and every attempt should be made to collect more while there was still time.

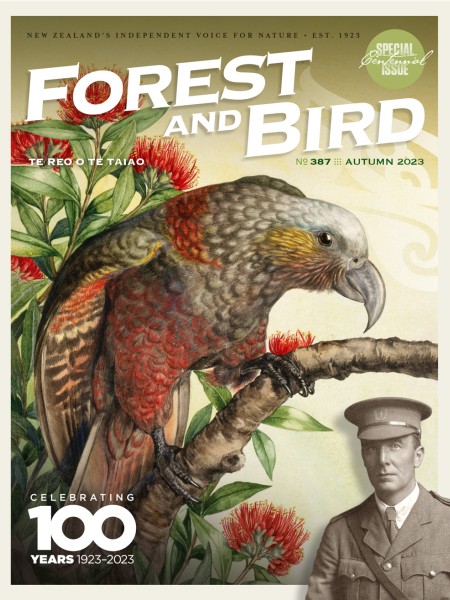

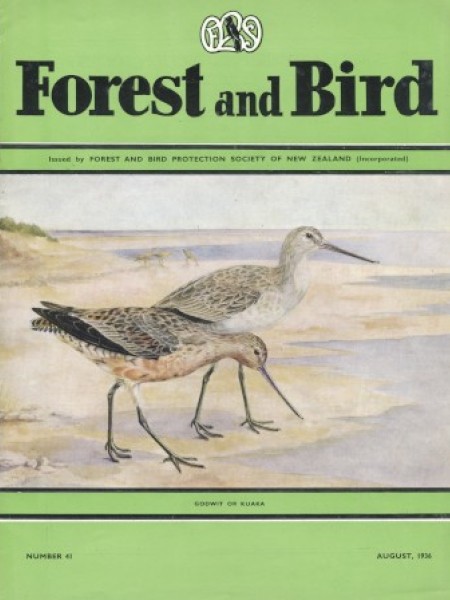

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Autumn 2023 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

A few months later, Sanderson discovered a Mr France was visiting from America to observe our bird life. He suspected the birds would be “observed” over the sights of a

shotgun. Firing off a letter to the Department of Internal Affairs, he discovered a permit had been issued in December 1925 for 846 New Zealand wild birds to be taken without supervision.

The list included six Chatham Island snipe, four Snares Island robins, and two Auckland Island ducks. Some species on the list had just 10 or 20 individuals left on Earth.

After a strong protest by the Society, with Sanderson working day and night on the problem, the Minister sent an observer – the same New Zealand official who had advised him to issue the permit!

But, as a result of the Society’s advocacy, a bigger battle was won. Early in 1926, the Minister agreed that “no collecting whatsoever would be permitted in sanctuaries, scenic reserves, and domains”. Permits would only be given to museums, and all foreign collectors would be accompanied by a government officer “experienced in bird matters and his expenses borne by the collector”.

It was one of the Society’s earliest “wins”.

Meanwhile, also in 1925, Sanderson was trying to persuade the government to designate the sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands a bird sanctuary. His first attempt, in 1925, failed because there was a £40-a-year grazing lease with seven years still to run. But he didn’t give up and carried on bombarding the government with letters.

“Should the natural beauties of the islands be damaged or destroyed, it would arise indignation in all civilised lands,” Sanderson wrote in one of his letters.

He sent scientific information about the islands’ unique flora and fauna gathered by the eminent botanist and Forest & Bird Vice-President Dr Leonard Cockayne. The Auckland Islands were gazetted a reserve in 1934.

Saving Saddleback

Tīeke saddleback, circa 1933. Image Lily Daff

In November 1925, Sanderson set off on an expedition to Hen Island, east of Waipu on the Northland coast, helping Forest & Bird stalwart Harold Hamilton, from the Dominion Museum, catch tīeke North Island saddlebacks.

The caretaker of Kāpiti Island, Stan Wilkinson, joined them. They captured 18 tīeke and took some over to Little Barrier, where they liberated them. The rest were taken to Kāpiti Island and freed there.

We’ve found evidence that Sanderson made arrangements with the station masters all the way back to Paraparaumu, via Whangārei, Auckland, and Palmerston North, to make sure the birds were safely transported to their new home!

In 1930, ornithologist Bob Stidolph reported that the saddlebacks were thriving on Kāpiti Island. Sanderson saw New Zealand’s offshore islands as essential refuges for species at risk of extinction, although he would later argue against the practice of moving birds around the country.

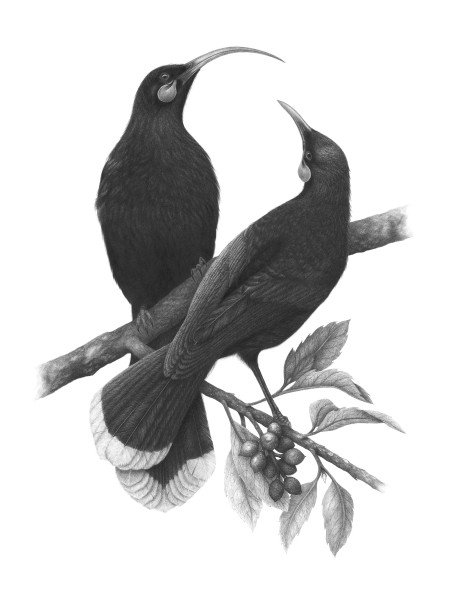

A Lost Harmony (Huia). Image Hannah Shand

In the 1920s, the loss of huia in 1907 was still keenly felt among conservationists. In fact, Sanderson would drop everything to lead expeditions into the bush to investigate reported huia sightings, as he did in February 1924, when he travelled to Akatarawa River, north of Wellington, but to no avail.

Deer menace

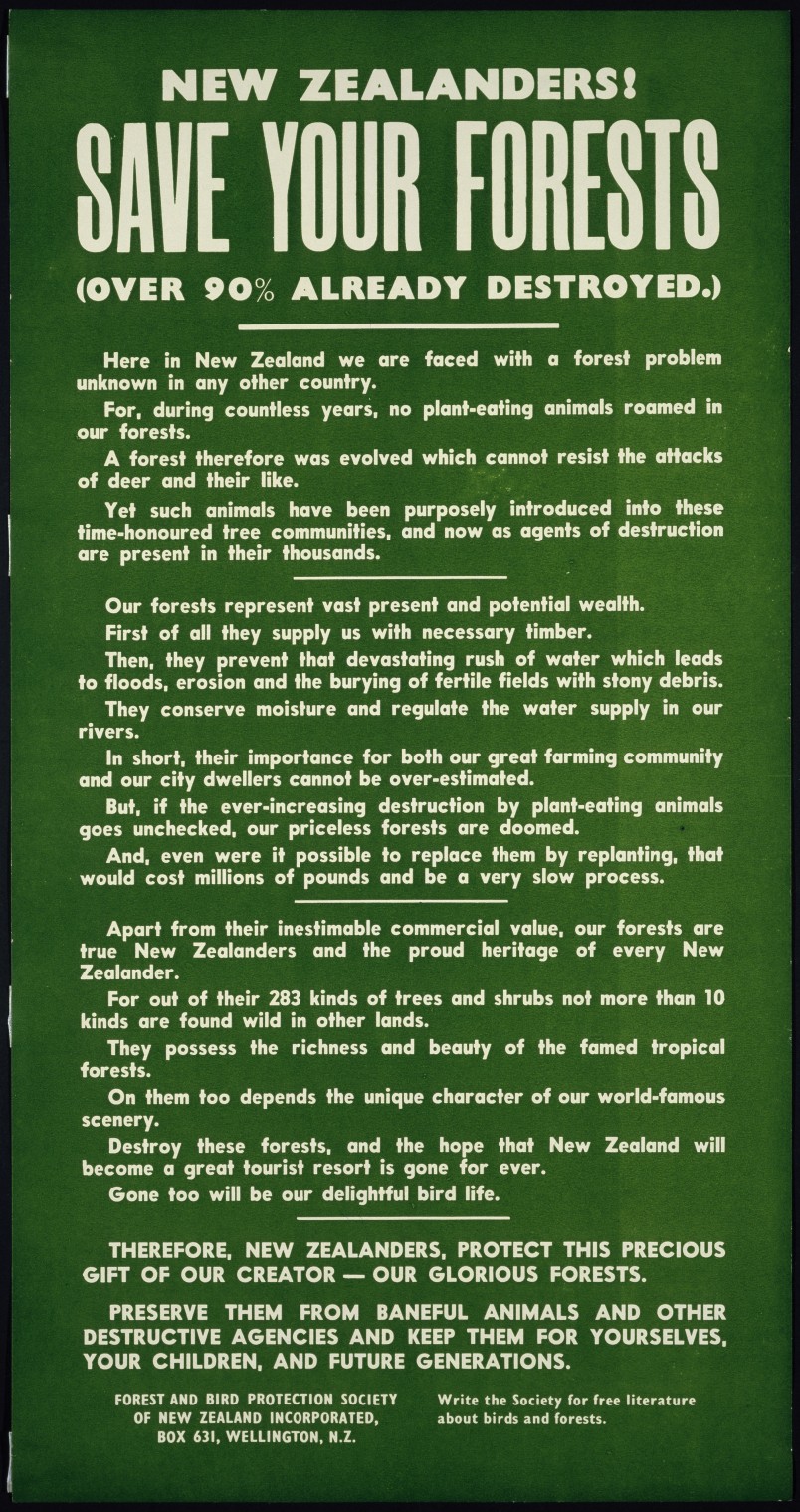

From 1923, the Society promoted science-based ideas and conservation solutions ahead of its time, including raising awareness of the damage “noxious animals” – introduced deer, goats, possums, cats, rats, and stoats – were making to native forests.

Sanderson, together with Leonard Cockayne and soil scientist Lance McCaskill (Vice-President, 1932), made it their mission to educate the public about what they called the “deer menace”. In 1930, the Society’s advocacy led to the government organising a Deer Conference in Christchurch on the impact of browsing mammals.

Sanderson and Cockayne attended along with other interested groups and several government departments. McCaskill sent two representatives from the Society’s Otago section. The government agreed the animals were pests and pledged “war on deer” at the conference. Ministers removed regulations that had up to this point protected browsing mammals and allowed free year-round shooting of deer, chamois, and tahr. It was another early win for the Society, which would continue to raise awareness of the impact of introduced pests.

In 1935, the Forest & Bird Protection Society wrote to every general election candidate in the country asking them to stop forest destruction in watersheds, saying it led to erosion, flooding, and poor water quality.

In the same letter, Sanderson also called for an extension of the government’s campaign against deer, pointing out the Department of Internal Affairs’ 9000 target was less than 5% of the annual natural increase of the pests that were ruining native forests.

“Is New Zealand for deer or for mankind?” he asked.

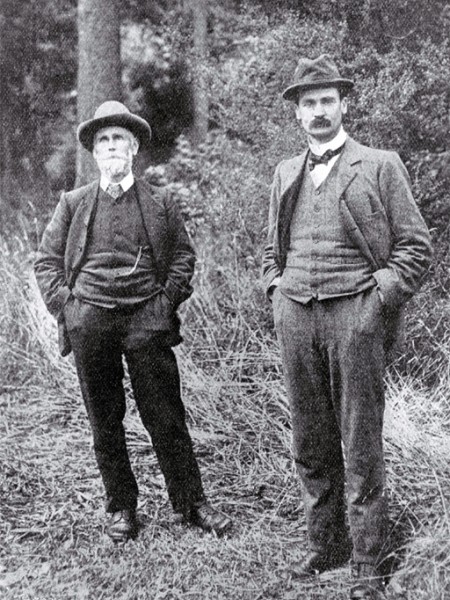

Leonard Cockayne (left) with Harry Ell MP, another well-known early New Zealand conservationist. Image Forest & Bird Archives

Godwit shooting

The journal was used to advocate for godwit protections. Image Lily Daff, August 1936

During the 1930s, Sanderson’s Society lobbied the government and acclimatisation societies, which issued shooting permits, for an end to wild duck hunting and for absolute legal protection for kuaka bar-tailed godwits.

At the time, it was still legal to shoot native ducks, including parera grey teal and pāpango black teal, as well as kuaka godwits and other visiting shorebirds.

Sanderson published articles in Forest & Bird’s magazine about the long-distance flyers and called for godwits to be added to the list of absolutely protected birds and for Pārengarenga Harbour, in Northland, to become a godwit sanctuary.

In an letter to the Minister of Internal Affairs in 1933, Sanderson said hunters were concentrating on certain species and extinction would result.

“Ducks were rapidly disappearing and godwits would follow,” he wrote.

The Minister refused to fully protect godwits from the gun but agreed to a shorter season, in 10 locations, with a bag limit of 20 a day. Sanderson said this didn’t go far enough.

“The slaughter of godwits is really a disgrace to New Zealand,” he commented.

After a prolonged campaign by the Society and others, kuaka finally received absolute protection in 1941. William Parry, the Minister of Internal Affairs, announced the move in December 1940, saying it was proposed “as a Centennial gesture, to place the godwit on the protective list”.

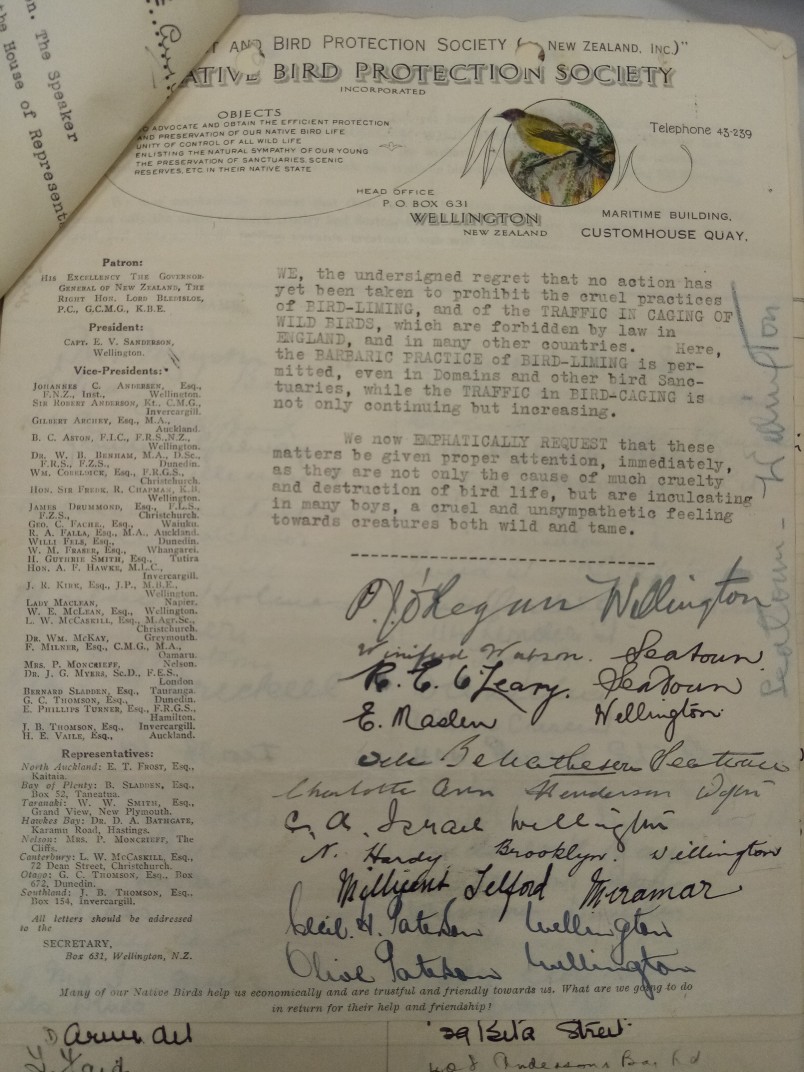

Bird liming petition

Forest & Bird cover prayer regarding bird liming petition

In 1935, Forest & Bird organised a petition signed by 8000 New Zealanders calling for an end to the horrific practice of bird liming. At the time, poachers and collectors were putting the sticky substance on branches to capture live birds so they could be sold to private bird collectors.

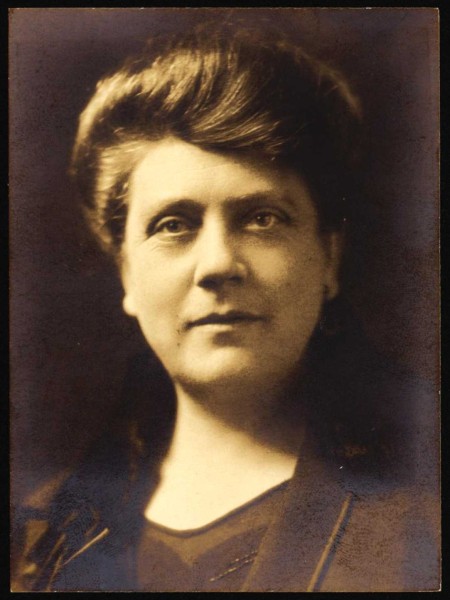

The petition was presented to Parliament by a group of Society members, including Elizabeth Knox Gilmer (pictured), the seventh daughter of former Prime Minister Richard Seddon, who helped collect signatures.

Elizabeth Gilmer's passport photo, 1925.

She was an active member of the Society and became a Vice-President in 1934. As well as an end to bird liming, the petition called for the abolition of wild bird trafficking. Mr Field, the MP who presented the petition, spoke in favour of it and pointed to the great cruelty inflicted by the liming and the loss to bird life.

Several other MPs spoke in support. The government’s Bird Lime Regulations were passed in 1936 and 1937, prohibiting the possession of bird lime or using it to capture birds.

Into the regions

In September 1923, Dr David Bathgate, of Turua, Hawke’s Bay, wrote to Sanderson enclosing a donation for £1, saying: “Many thanks for your various pamphlets and letters which I have received and read with interest. Your society is one with fine ideals and praiseworthy objects ... I hope to see branches formed all over the Dominion, especially among the children and their teachers.”

Sanderson initially resisted the idea of setting up branches but was keen to appoint official regional representatives to advocate for nature in their local areas. One of the first appointments was Mr JB Speed, who became the Society’s Auckland representative in 1924.

The first known Forest & Bird branch was established in 1928 in Raetihi by Tom Shout but didn’t last long. Then, in 1930, Sanderson arranged for meetings in Dunedin and Invercargill to form the Otago and Southland branches. They both closed within a few years, possibly casualties of the Great Depression, only to re emerge as branches two decades later. In 1934, the Society’s magazine started publishing the names of its regional representatives: Bernard Sladden, in the Bay of Plenty, WW Smith, in Taranaki, Perrine Moncrieff, in Nelson, Leonard McCaskill, in Canterbury, George C Thomson, in Otago, and JB Thomson, in Southland.

This 1929 Forest & Bird poster was displayed at tram and railway stations.

After World War Two, branches and sections started popping up all over the country. The Canterbury section was first in 1946, followed by Auckland and Gisborne sections in 1947. The 1950s saw branches established in Dunedin, Wellington, Waikato, Tauranga, Whanganui, Tarankai, Hastings-Havelock, Napier, Whakatane, Rotorua, Manawatū, Northland, and Timaru. More branches and sections sprang up in the 1960s and 1970s.

Unity of control

In 1923, Sanderson’s primary objective was to secure “unity of control” of all wildlife. He believed having a single agency in charge of nature protection was the most effective way to protect the birds and bush.

Nearly 45 years later, his dream came true following a campaign by a group of e-NGOs, including Forest & Bird.

The Department of Conservation – a world first – was established in 1987, with one third of the New Zealand’s land put into the public conservation estate. It was an incredible achievement and one that Sanderson would have warmly welcomed, although he probably would have said it wasn’t enough!

These stories could not have been told without the assistance of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Archives New Zealand, and many regional museums and local archives. We are also grateful to the Stout Trust for their support of Forest & Bird’s Force of Nature history project.

In future issues

New Zealand’s unsung women heroes of conservation • The importance of children in Forest & Bird’s history • Saving kea: from bounty kills to bountiful love • The power of publicity: how early Forest & Birders inspired a nation to love nature.