Young people have played an important but overlooked role in conservation

over the past 100 years, says Emma Graham.

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Spring 2023 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

Children and their education are a key component in conservation practices in this country, and Forest & Bird has always made efforts to facilitate the involvement of youth in its conservation work.

As a Master's student, I was interested in the impact of children in Aotearoa New Zealand’s environmental history over the past century but found that, despite children’s importance to conservation today, there had been little academic research on the topic.

I chose two distinct time periods, 1923–1940 and 1988–2019, to look at why and how children were encouraged to become involved in advocating for nature – and whether this changed over time. I used Forest & Bird’s journals, correspondence, photographic archives, and newspaper articles as a basis for my research.

By examining children’s standing in the oldest national conservation organisation, I discovered many continuities in the role children played in conservation over the past century but some key differences too.

From 1923 until 1940, children’s involvement in environmental issues was encouraged but only when it aligned with other social, political, and economic agendas of the day. For example, planting a tree on Arbor Day was seen as a patriotic act, as well as being good for the birds and economy.

Early conservationists did provide important, ongoing education specifically for children, allowing them to develop their own opinions and desires to be involved in conservation. Many went on to become lifelong nature champions.

But there was a dramatic step change in Forest & Bird’s approach towards involving children in conservation in 1988, when it established the Kiwi Conservation Club, the first national children’s conservation organisation in Aotearoa.

This was built on a very different foundation – the belief that with the right encouragement children could make meaningful environmental change themselves. This saw children taking on a role that was much less driven by adults and much more about their own sense of connection to the natural world.

Then, in 2016, Forest & Bird’s Youth Hubs were established for 14–25-year-olds. These groups are organised and led by young people.

Although this change is indicative of progress, thereis still work to be done – for example, by reviewing the way we teach children in schools about their role and importance in Aotearoa New Zealand’s conservation history.

Perhaps our attitudes towards children in conservation need to change too, if we are to face the challenges of the future with a fighting chance. If given the right support, children can be powerful voices for nature in their communities.

Emma Graham (née ten Have). Image supplied

In 2019, Forest & Bird awarded a Force of Nature history project scholarship and archive support to Master's student Emma Graham (née ten Have), of Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington, to research the contribution of children in environmental history. Emma delved into the Society’s archives for her 10,000-word research essay A century of Children’s Involvement in New Zealand Conservation: The Role of The Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society. The following pages are based on Emma’s research and findings. Thank you to environmental historian Dr James Beattie for supervising Emma’s research.

PLANTING A SEED (1923-1940)

Today, there is a growing youth-led environmental movement in Aotearoa New Zealand, but the role of children in conservation is not new. From its foundation in 1923, Forest & Bird focused on educating children about nature. This kaupapa continued throughout its history, evolving and adapting with the landscape itself.

The early Forest and Bird prioritised children, who founder Ernest “Val” Sanderson described as possessing a “natural sympathy” for wildlife, and he made every effort to reach out to them. Others supported him in this work, including his friend and Vice-President Pérrine Moncrieff, ornithologist, bird advocate, and Girl Guide leader.

The Society offered a one shilling child membership and special rates for families and schools, and campaigned for a bird day in schools. Sanderson also published bird posters and books for children, while providing written resources to teachers.

"The New Zealand Native Bird Protection Society has decided wisely that bird-lovers are made as well as born. By devoting their attention to schoolchildren, Boy Scouts, country leaders, and especially to the School Journal, the members of the Society are creating the sentiment without which laws are of very little use."

One of its first child-focused publications was the poster Young New Zealanders Protect Your Birds! Published in 1923, it was sent to 2000 schools and is the first instance of the Society endeavouring to show children what native birds looked like.

A dedicated children’s page was included in its magazine from 1926, an initiative of founder member and Vice-President Arthur Messenger, a talented artist and writer. Later the Junior Section would be written by children themselves.

Perhaps the most pressing issue for the early Forest and Bird was the need to put a stop to harm to native birds by “young vandals”, including stealing eggs. It achieved this by establishing bird clubs in schools and sparking an interest in their protection.

Young New Zealanders poster, 1923. Image Te Papa (CA000450)

Nevertheless, there remained a few bad eggs. One newspaper article described a Taranaki teacher’s horror at finding some of the boys in her class “swinging nestling birds by the head until they were decapitated” (Bay of Plenty Beacon, 1940).

The teacher questioned the children, who replied that “their father had told them birds were no good”. She made 12 of the boys members of Forest and Bird and instructed them to read the quarterly magazine. The boys later became the driving force behind the protection of native birds in the district.

The School Journal, which was established in 1907, always supported Forest and Bird initiatives and the conservation cause in general.

In Forest & Bird’s archives, there are countless letters to Sanderson from various teachers asking him for literature and photos that will be appealing to children who are “keen naturalists”.

Cover of Birds magazine, 1930, featuring Pérrine Moncrieff.

Sanderson always responded enthusiastically. He provided information on what to feed native birds in a child’s garden and identification of birds based on children’s descriptions and encouraged children to study their habits and form their own “Bird Clubs” in schools.

In 1928, Forest and Bird established an essay competition in its magazine for children to write about their own observation of a bird and its habits. Some of the winning essays were published, and the winner received a £5 prize.

An essay from the Chatham Islands emphasised the “shamefulness” of destroying the native pigeon, pointing out their value in seed distribution.

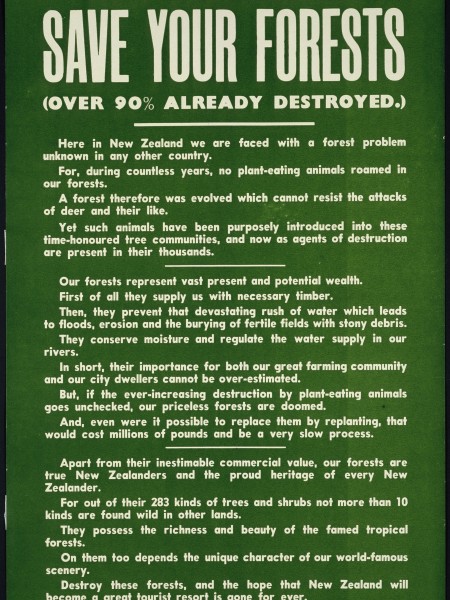

This poster was first published in 1929 and reprinted in 1934 in this lovely green colour. It was 2ft long. About 3000 were distributed with the School Journal in 1930s. The poster’s words were written by Sanderson and Leonard Cockayne, and its publication marked a shift in the Society’s focus from birds to include native forests. The wording invoked a call to patriotism and emphasised the importance of forests in supplying timber and for farming, birdlife, and our world class scenery. Image Alexander Turnbull Library

Why did the early Society prioritise children so adamantly?

The answer lies in the context of a newly settled country, which was heavily focused on breaking in the land for farming and production, making adults difficult to reach with environmental issues, according to New Zealand historian Kirsty Ross.

Adults who had a sense of connectedness to the land, and a desire to save it, turned to children, who, they reasoned, were more willing to listen and learn, Ross argued.

As New Zealand-born Kiwis began to identify with indigenous nature, there was a growing sense of instilling into children a love of natural heritage as a way of ensuring they carried this patriotism into adulthood, says historian Paul Star.

Sanderson’s ties to Scout groups in New Zealand and the Society’s support of planting initiatives, such as Arbor Day, were part of the movement to educate children about the environment as a form of patriotism.

The New Zealand Scouts Association, which wanted to encourage a love of nature and respect for animals among its young members, formed an early alliance with Forest and Bird. It later created a bird warden proficiency badge.

In the late 1920s, Sanderson wrote to Scouting leader Roy Nelson, later President of Forest and Bird, saying: “You will find the bird and forest work of great interest to the boys. It will be their work to look after them someday and we wish you every success.”

Scout groups helped distribute the Society’s posters, taking them into the remote places. In 1932, Sanderson supplied them with posters and galvanised tacks so they could put them up in tramping huts and on trees where birds might be found.

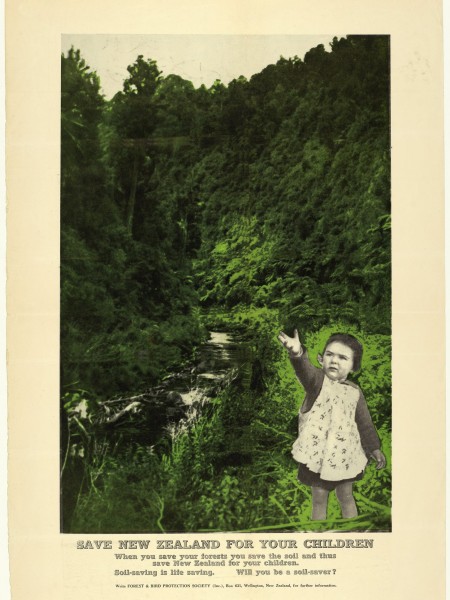

Val Sanderson’s daughter Ruth superimposed over native bush, 1938. Image Alexander Turnbull Library

During his 20-year leadership of Forest and Bird, Sanderson repeatedly spoke, with a sense

of urgency, of the need for adults to save New Zealand’s nature for their children. In 1938, he published a poster and advert featuring his daughter Ruth with the tagline Saving New Zealand for your children.

Although a bird day in schools never eventuated, the Society did launch Bird Month in August 1931, and it ran for 15 years, a precursor, perhaps, to Bird of the Year.

Over the first two decades of Forest and Bird, Val Sanderson and his fellow volunteers helped instil a love of nature in children, highlighted the need for environmental education to be included in schools, and created written and pictorial nature resources specifically for young people. The Society also worked with the Scouting movement, schools, and other organisations to encourage children’s participation in hands-on conservation activities, including planting and bird care efforts, while encouraging their parents to cherish their forests and birds for future generations.

In the Summer 2023 issue

Emma Graham looks at the birth of Forest & Bird’s Kiwi Conservation Club, which prioritised child-centred conservation, an approach seen as a key milestone in environmental education in Aotearoa.

TŌTARA TRIBUTE

Wellington College organised a heartfelt ceremony in memory of Forest & Bird founder Ernest “Val” Sanderson and its legendary headmaster JP Firth.

From left Alex Greenwood, Kate Littin, Glen Denham, Eddie Fraser, Tai Renner. Image Caroline Wood

Val Sanderson was eight when he started as a paying pupil at Wellington College in 1874, the year the school opened at its current site next to Government House, in the capital. For the next 10 years, he would take the short walk from his family home, in Brougham Street, to attend classes.

Sanderson, a keen cricketer, helped its longestserving headmaster JP Firth develop a muddy swampy ground into a sports field.

The school and its grounds would have been a place of safety for Val and his brother Louis as their home life was unhappy, with a violent father.

Joseph Firth had a hugely formative influence on all his boys, including the Sanderson brothers. He cared for them as individuals and encouraged them to take an interest in their own education.

After retiring, Firth became a founder member of his former pupil’s Native Bird Protection Society of New Zealand, when it was established in 1923. He stressed the value of teaching children about nature, edited the fledgling magazine, and campaigned to restore Kāpiti Island.

Firth died in 1931, and, when his wife Janet passed away in 1939, she left £100 to the Society, the equivalent of $17,000 today. Sanderson paid tribute to the couple, saying they were “enthusiasts for the conservation of New Zealand’s forest and bird life”.

Wellington College Old Boys Association organised a commemorative tree-planting to mark Forest & Bird’s centennial.

Our Wellington Branch donated the tōtara, which was raised from wild-collected seed in its Highbury Nursery. Volunteer Richard Grasse, who taught at Wellington College for 10 years, manages the nursery. A plaque in memory of Sanderson and JP Firth was blessed and unveiled.

Arbor Day at “Coll”, 1 August 1934. Image Wellington College Archives

Old Boys Association President Ted Thomas said: “We wanted to pay tribute to Val Sanderson, one of our early conservationists and founder of Forest & Bird, who has played an important role in the history of New Zealand. He is another of our 33,000 Old Boys to have made a significant contribution to the nation.

“Val also made a significant contribution in helping our longest-serving Headmaster JP Firth (1892-1920) develop what was a muddy, swampy ground to the sports field the College has today. The link between the two continued long after Firth retired in 1920 as Sanderson battled with government departments to restore Kāpiti Island.”

Wellington Branch chair Kate Littin, whose son Eddie Fraser is a pupil at the school, thanked the Old Boys Association, college archivist Mike Pallin, headmaster Glen Denham, and the prefect team led by headboy Tai Renner for a wonderful tribute.

The tree-planting took place 89 years to the day that national Arbor Day was re-established by Elizabeth Gilmer, a Forest & Bird Vice President, as a way of engaging children in a love of New Zealand’s flora and fauna, and promoting responsible citizenship.

Gilmer, who was the daughter of Prime Minister Richard Seddon, organised for a tree planting to take place at Wellington College, and used her contacts to invite the Governor-General Lord Bledisloe, who popped over from Government House to attend.

Forest & Bird sent three representatives to the event on 1 August 1934, including Val Sanderson. Together with many enthusiastic shovel-wielding pupils, they planted the pōhutukawa trees still flourishing today in front of the school, outside Firth Hall.