Forest & Bird’s Save our Seabirds team moved quickly to find the culprit when a dead sooty shearwater chick was discovered. By Kerrie Waterworth

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Winter 2024 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

Four ferrets have caused carnage at Sandfly Bay Wildlife Reserve on the Otago Peninsula since March, killing at least 41 tītī sooty shearwater chicks and seven adults.

They struck when this season’s chicks were about two months old and defenceless in their burrows, waiting for their feathers to grow so they could fledge. Many adults had already set out on their annual migration across the Pacific Ocean.

Forest & Bird manages a Save our Seabirds project on the headland tītī breeding colony, one of the few mainland breeding colonies left in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Chicks that survive will launch themselves off the steep cliffs overlooking the Southern Ocean and head out to sea, returning seven years later to the place they were born to find a mate.

Save our Seabirds project manager Francesca Cunninghame said it was the first time more than one ferret had been recorded at the Sandfly Bay colony since trail camera monitoring began in 2018.

“As soon as we found the dead chicks and realised ferrets were present, our team activated our intensive trapping response,” she said.

“We caught three ferrets in quick succession, but the fourth ferret surprised us. It navigated its way through the intensive trap network and didn’t interact with any of the traps.”

Sue Maturin and Francesca Cunningham remove a dead chick killed in its burrow by a ferret. Image Graeme Loh

Even Almo, a Department of Conservation mustelid dog, and his handler Ange Newport could not locate the elusive ferret when they visited the reserve on 7 May.

“But they did identify the travel lines of the ferret around and within the colony, so we are now better informed where to place the traps to try and catch the ferret,” Francesca said.

“Almo also lead us straight to a cache site where the ferret had stashed three unbanded chicks that we did not know about.”

In 2021 and 2022, more than 100 chicks fledged successfully from the colony, but sadly this breeding season ferrets killed at least 48 tītī (41 chicks, 7 adults), leaving only 13 fledged chicks.

Francesca said they do not know exactly where the ferrets are coming from, but Sandfly Bay Wildlife Reserve is surrounded by farmland with a large rabbit population, and rabbits are the key food source for ferrets.

“Ferrets are capable of travelling a long way and can easily reach the coastal sites all along the Otago Peninsula, where a range of threatened native and endemic seabird species breed,” Francesca added.

Ferrets are not the only threat to tītī trying to breed at Sandfly Bay, one of the few remaining mainland tītī colonies. Rats, mice, possums, cats, stoats, weasels, and even hedgehogs predate on tītī sooty shearwaters, chicks, and eggs.

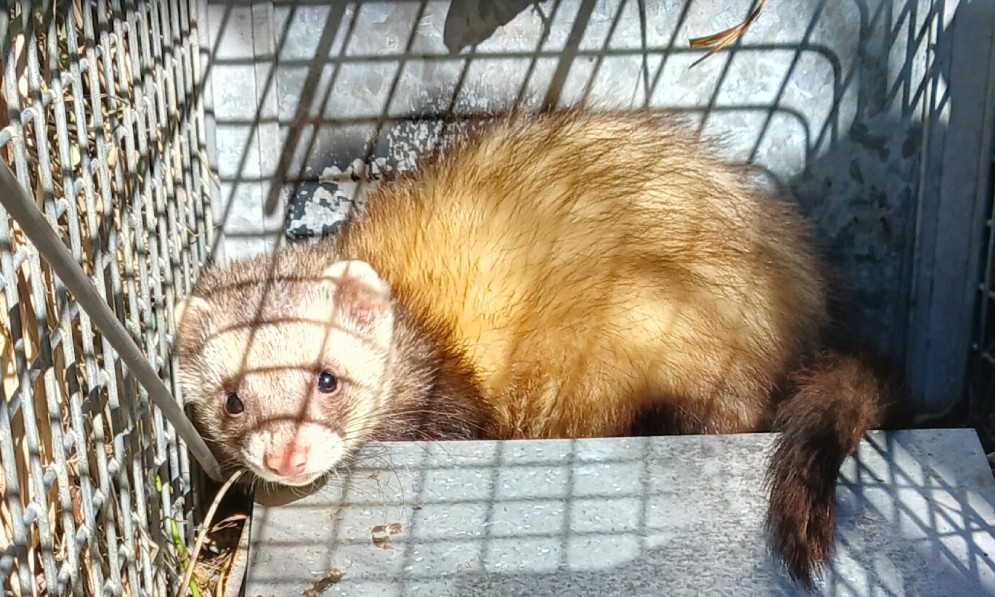

The team caught three of the four ferrets that were terrorising the tītī breeding colony. Image Will Perry

But a single ferret can kill multiple chicks and even adults in one night and repeat the same behaviour over successive nights.

Tītī sooty shearwaters have one of the longest migrations of any seabird, flying across the Pacific and up the west coast of the United States of America to their North Pacific Ocean feeding grounds.

Breeding pairs arrive back in Otago in October, but it is about seven years before chicks return to breed at the Sandfly Bay colony.

Healthy tītī in burrow before fledging. Image Francesca Cunninghame

“Our challenge right now is to use all the information we have to work out how best we can target this individual ferret as soon as possible to prevent it reappearing around the colony next breeding season,” added Francesca.

“Close monitoring of this ferret’s behaviour will contribute to the growing pool of knowledge about individual predator behaviours and how this relates to wider scale predator-free ambitions.”

Trail cameras filmed one of the ferrets going into the burrow, dragging out the tītī chick, and killing it. This short video is hard to watch but shows the impact one ferret can have. View here.

EYE IN THE GROUND

Burrowscape image of a sooty shearwater chick in its burrow. Image Francesca Cunninghame

Staff and volunteers at Forest & Bird’s Save our Seabirds projects in Otago are using the latest technology to check on the welfare of tītī chicks.

As well as trail cameras that record intruders outside the burrows, Francesca and her team use a burrowscope to look deep inside them.

These consist of a miniature camera and infrared lights mounted on a 3m length of hose through which images are projected on to a screen at the surface.

“It is challenging to burrowscope the burrows at this site. They are in sandy substrate and can easily be more than 2m long,” explained Francesca.

But it’s an invaluable tool to understand the extent of a predation event. During the recent ferret incursion, Franny discovered the majority of chicks had been killed and left inside burrows.

But the team found some survivors too, and they went on to fledge successfully.

If you want to help Francesca and her team of volunteers save our seabirds, please go to forestandbird.org.nz/donate and make a gift for nature today.

⏎