by Michael Pringle

When first asked to help with the Forest & Bird History project I knew that my experience in working with a range of archival sources in New Zealand would be useful to Forest & Bird.

The principal objective of the project was to complete a centennial history of the Society as it approached its 100-year anniversary in 2023. Secondary to that was the task of getting Forest & Bird’s own archives into order, which were in several different locations and not always stored in the best conditions.

Lance McCaskill at Tongariro National Park. Image courtesy of the Blackman Family

Once the book was scoped, I began the task of identifying the sources for the stories that we wanted to put into the book. In the 1980s and 1990s most of the Society’s records from about 1893 to 1982 were deposited with the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington. I began identifying key files and making notes. The letters of Lance McCaskill, a confidant of Sanderson’s from the earliest days, were one of the key sources, because Lance continued his voluntary work for Forest & Bird right up until his death in 1985. His frank and personal letters reveal decades of work with schools and training colleges to educate children and teachers in nature conservation. He and Sanderson maintained a regular, detailed correspondence, and Lance’s ideas continued to be influential in the development of Forest & Bird after Sanderson’s death.

Also important were the records of the Society’s executive over the years. From the first meeting in March 1923, decisions were recorded, and personalities came and went. The minutes proved to be an invaluable source of accurate facts and dates. Patient checking of the minutes, month by month, proved a link between the first and second Forest & Bird societies, when we found a transfer of the residual funds of the first society to the second, made in 1939.

What had been catalogued as “index cards” in the Turnbull collection were actually the subscription record cards for members from about 1930 to 1960. We have turned to these eight boxes of cards again and again to find the join dates and histories of some of our earliest members.

Pérrine Moncrieff's membership card. Among her many achievements was her role as one of Forest & Bird's early vice-presidents and leading the campaign that secured Abel Tasman National Park in the 1940s.

The organisation of the Forest & Bird records at Turnbull reflects the way that the Society officers had organised records over the years. The deposit had been taken in with very little further arrangement and description. Thus, the organisation is a little haphazard (though not without a system) and checking for the records of an individual often required looking through a number of letter series. For instance, the letters to and from Lily Daff were found in the Foundation Members letters, general correspondence, and the files on publicity and books. Only a little is in the file marked “Lily Daff.” The discovery of more of her letters shed new light on her career and these files can be used by future researchers to assemble a more detailed account of her life. I hope this task will be taken up by another researcher, for that is a story that must be told.

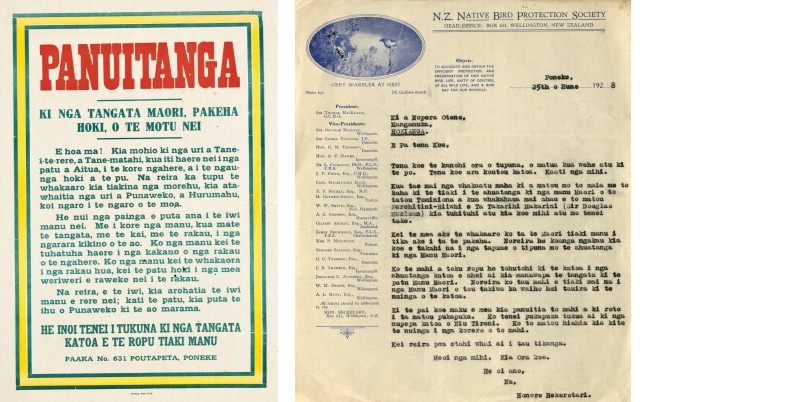

The folder called “Māori letters” proved a treasure trove, revealing much about the work done by Sanderson with Māori in the 1920s and 30s. Once the people involved in that story were identified, further letters from them were found in other parts of the letters archive. We indexed and cross-referenced the “Māori letters” in order to build up a more complete picture, which was described in a Forest & Bird story published in the Winter 2022 issue.

Forest & Bird's 1924 panui poster (left) and Val Sanderson's 1928 letter to Otene in te reo (right). Forest & Bird archives.

Record-keeping processes naturally changed through the decades, and became more systematic, which made finding more recent material easier. Eventually, I looked at every single one of the 1,150 folders of Forest & Bird material at the Alexander Turnbull Library – sometimes several times. There is a still a great deal to be found in the letters, and therein resides a vast reservoir of stories for future researchers.

What became clear from looking through the numerous letter folders was the sheer number of correspondents to Sanderson from the formation of the Society in 1923, through the 1930s and 40s. Letters came from people in many walks of life and from all over New Zealand, often in very remote spots, recording the bird sightings in their locality or the state of the forests and native vegetation. Often, people noted the visits of birds to their own gardens, and the success or otherwise of the bird feeding techniques that were explained and encouraged in the society magazine. Many of them required detailed answers from Sanderson. It was not long before he required paid secretarial assistance to keep track.

Dr Leonard Cockayne and Harry Ell 1904 (left, courtesy of Christchurch library) and Harry Ell's 1914 letter to the Prime Minister urging the preservation of the Poor Knights Island (right).

As the scope of the book began to take shape, we identified several stories that needed more in-depth research. The files at Archives New Zealand (ANZ) were consulted to find the earliest letters that Harry Ell wrote to Ministers imploring that islands, remarkable features of landscape or tracts of forest be saved. Ell’s letters regarding the Poor Knights Islands, for instance, were found at Archives New Zealand, along with photographs related to the pig hunting expeditions in the 1920s by William Fraser, also of Forest & Bird. By then, the government was committed to ridding the islands of pests, and pig hunting continued into the 1930s, when all the pesky porkers were finally dispatched. The photograph shown on page 21 of the book is one of a set of photos taken by Fraser and others on the 1924 expedition, which were found in the Poor Knights file at ANZ. Ell’s letters regarding the Waro Rocks and extensions to the Tongariro National Park around Ohakune are also at ANZ. Thanks to Ell’s dogged persistence, frequently the files became voluminous as various government officials were consulted for advice and the correspondence flew back and forth. Rarely did Ministers give way at the first demand.

Letter to Sanderson enclosing kakapo feather (1925).

Occasionally we’d turn up an oddity in the archives: we found a kākāpō feather in the letters files at the Turnbull (see Forest & Bird Spring 2020), examples of children’s badges, and a gecko skin attached to a letter in the Poor Knights letters file at Archives New Zealand in Auckland, later identified by Colin Miskelly of Te Papa as from a Dactylocnemis gecko.

The archives of Te Papa Tongarewa the Museum of New Zealand also proved useful for our book.

There in the files of letters from Sanderson to early society supporter John Myers I found the very first poster that the NBPS ever produced: the 1923 poster that was sent to schools. We believe that it is the only copy in existence; it is the only one that has been found. After it was found, and its importance explained, Te Papa digitised the poster, and it appears on the Collections pages of their website as well as on page 54 of Force of Nature. Also at Te Papa archives, we found evidence that early meetings of the ‘first’ Forest and Bird Society (1914-1919) were held at the Dominion Museum. This was found by poring through the daily logbooks of the Director of the Museum, James Allan Thomson, who was a Council member of the first Forest and Bird.

This poster, first published in 1923, was reprinted several times in different colours. Credit Alexander Turnbull Library 84-180-62

Of course, Forest & Bird’s own archives at the national office were to prove of great interest. Early on many of the photographs we own were scanned in – these are slides, prints and negatives. Many of these are used in the centennial history book. Drawers of posters were catalogued, and some were scanned in and appear in the Force of Nature book and have been described in articles in Forest & Bird. The records of Forest & Bird’s own lodges and reserves were still held at head office, from the date that they were donated, and this enabled us to build up an accurate history of each one.

Branch records are found both in the collections at the Turnbull Library and at head office, but we are currently transferring many branch records to the Turnbull for the period from 1981 up to about 2002. These will be valuable for future researchers who may come to write the history of their own branch. Branch records are held consistently as all branches were required to report closely on their activities to head office from the day they were founded (initially as Sections), and the letters often make for interesting reading. We were able to use the Southland branch records, for example, in telling the story of Big South Cape and the rat extermination in the 1960s. The detailed minutes kept by the branch secretary enabled us to identify the individuals involved and exactly what they did, so they are given their proper credit in the history.

Val Sanderson (R) with unknown friend, early 1920s (colourised and cropped)

By no means least were archives located in the possession of family members. The family of Capt. Sanderson, especially grandson Justin Jordan, have provided us with a continuing stream of fascinating finds from the attic in Justin’s house. Photographs and even films taken by Sanderson have been digitised. Always ready with his camera but reluctant to appear in front of it, Justin’s boxes of old negatives have proved a goldmine for photographs of Sanderson. Other photographs were located by the Webber family, and one is a scan of a lantern slide made by Sanderson himself of the Webber house on Kapiti Island which was located among a box of Society lantern slides unearthed at the Mavtech museum in Foxton.

Family members were most generous in giving up their time to locate just the photograph we needed for the book in their own collections – the lovely photo of the Hutchins that appears in the book, the Merton family for the photos of Don Merton, the Shand family for the “high country sisters” photo (see below) – the list is long.

High Country sisters, Lesley and Diana Shand, on family farm with tiny pet lamb Moss (circa 1946-7)

Long-serving members, such as Timaru’s Fraser Ross, have long had photograph collections in their possession and we were able to utilise some of Fraser’s photos for the story on the kakī black stilt.

We are deeply grateful to these family members, and to staff at the many museums and libraries we regularly pestered for hard-to-find photographs, who were unfailingly willing to help.

Mahanga, a young Māori pig hunter on Tawhiti Poor Knights Islands, 1924. Photo taken by Forest & Bird's William Fraser during an expedition to remove pigs from the islands to protect rare birds, snails and native lizards.

Finally, the growing pool of online resources proved a boon to our research. The photograph collections of the Turnbull Library, and those available via DigitalNZ, were frequently accessed. Kura at Auckland Public Library is also a very useful database. At Ngā Taonga the Film Archive we found the films that Forest & Bird made through the decades. We frequently used Papers Past to check dates and cross-check information. With creative use of search terms, it can be used in all sorts of inventive ways, to find a person or date an event or photograph. The possibilities are truly limitless. We even used it to find items within our own Forest & Bird, now also on Papers Past, so much more quickly than leafing through many issues of the journal would allow.

Paper records will continue to be invaluable, of course, and finding aids and good catalogues remain essential in finding the right archive. Not all records ever will, nor should they, be digitised. Persistent searching, finding the trail and not letting go, will always be required! As the great American biographer Bob Caro many times said, the secret to his outstanding biographical works was to “turn every page.” That is still what it takes.

Buy the Force of Nature book

To read more about these and other fascinating stories we unearthed, buy a copy of Force of Nature from the Forest & Bird shop. All the book’s profits go towards the Society’s conservation mahi.

READ MORE

Article: Force of Nature book published

Extract: Arthur Harper, old-school naturalist

Extract: Carole Long, fight the policy not people

Extract: Birds with attitude: rediscovering takahē

Extract: Becoming kaitiaki: Hone McGregor

Just one of the many boxes from the Forest & Bird archives. Credit Michael Pringle