Four years ago, Silvia Pinca embarked on an ambitious project to almost single-handedly rewild a freshly logged pine forest. This is her story.

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Summer 2023 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

Thirty-eight thousand and seven hundred pines removed and counting ... I was puffing, backpack on shoulders, handsaw in hands. “Why had I decided to do this?” I asked myself. This was way harder than what I had envisioned.

In 2019, two years after the neighbours felled the pines from a 30ha lot on the other side of the fence, I decided to purchase the property and “help” it come back to natural health – ie, to rewild it.

To start with, I faced about 40,000 pines, regrown two years after the felling. Removing them involved many days of hard hand-sawing on steep, heavily damaged hillsides, wobbling over logs, not-yet-rotting branches, forestry slash.

After making some space, the following years I focused on the more uplifting job of planting mānuka to create a ground base for other species: pūriri, kōwhai, kawaka, tōtara, pōhutukawa, and more. Compared with the earlier devastation, these new plantings, along with the self-regenerating bushes and trees seeded from the next-door forest – our own home-bush reserve – were a joy to see.

But every subsequent year brought a new challenge.

While the pesky pines re-sprouted in fewer and fewer numbers and are almost non-existent today, the invasive pampas grass, moth plants, woolley nightshades, passionfruit, and banana passionfruit invasions became more daunting. Even with intensive eradication actions, they keep coming back.

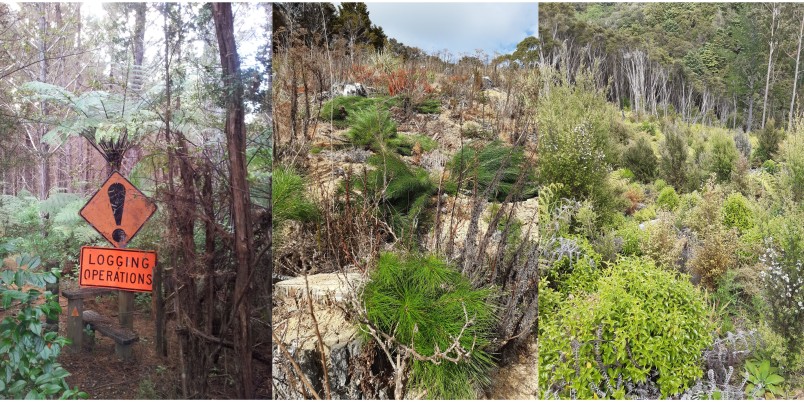

The land before, during and after Silvia's forest restoration work (L-to-R): 1 exotic pine forest 2 rewilding pines two years later 3 native trees are flourishing today.

Why did I embark on such a challenging project? In my earlier life, I was a marine biologist contributing to the conservation of tropical coral reefs and their subsistence fishery. I quit a decade ago, having lost hope in governments taking the right decision for long-term preservation of nature and the natural resources that support humans.

After studying and applying natural health, I felt called back to nature, my first passion, and I now focus on restoring impoverished biodiversity and habitat, both critical life-supporting assets for future humans. Loss of biological complexity impacts the basic elements of life – oxygen, water, food – and beauty too.

Biodiversity, in the sense of richness of species, niches, ecosystems, or life complexity is shrinking fast. The main culprits are the invasions of exotic species and habitat degradation by deforestation, overfishing, building (roads, factories, megacities, etc), and pollution.

Silvia Pinca on her trusty quad bike. Image supplied.

My husband Nick, a fisheries biologist, has been living here in a sustainable manner for the past 25 years, trapping invasive species (possums, rats, weasels, stoats, pigs, and wasps) to preserve tree roots, foliage, and native birds. The forest thrived and the birds came back.

He and a friend started Tutukaka Land Care Coalition, a charitable trust that has been enhancing local biodiversity. The group has encouraged other local organisations to carry out pest control, and kiwi and forest conservation in a large area of Northland.

Inspired by these dedicated people and by my heartfelt need to repair some of the damage to nature, I created a project that could also address another big worry: the impact my lifestyle has been having on the degradation of nature and climate change.

I decided this land was going to absorb my past and present emissions – native trees not only host indigenous animal species, from bacteria to birds, but also produce matter from CO2 absorbing it from the atmosphere.

More than 6000 invasive pampas grass were removed. Image supplied.

It might have been frightening to tackle this solo, but I gave myself no choice. The hardest part was pulling, cutting, and pasting weeds, collecting thousands of moth and passionfruit pods, scrub-barring and spraying more than 6000 pampas grass, carrying thousands of mānuka and kānuka seedlings on my shoulders to the different corners of these hills.

And I was not always on my own. I had to ask for local help in some instances: a neighbour with his chainsaw was hired to tackle the largest pines that my pruning saw could not decapitate, and Nick, improvised hunter, saved my newly planted seedling from herds of wild pigs invading the property and rooting all over it.

Thanks to Trees That Count, Carbonclick, many private donors, and a few volunteers, I was able to purchase and plant more trees, while Northern Regional Council and Cut’n’Paste provided herbicides and traps. It meant I could go quite far in restoring this space.

Today, the land is no longer dominated by drying pine logs and piles of broken branches attempting to dislocate my ankles but is increasingly covered by native trees and shrubs, green new leaves, and flowers everywhere.

There will be times of drought, like in the past El Niño, and periods of heavy winds, cyclones, and who knows what this climate has in store for us. But this still felt like a much-needed effort to slow down and reverse the damage we humans have caused the environment, as well as compensate for old ways of living on this planet, an unsustainable way of life still being lived by far too many.

Thousands of native plants were dug into the ground by hand, including 4900 trees. Image supplied.

Silvia Pinca lives at Te Rapa Sanctuary, a pristine 140ha of native bush in Northland. Her geodesic dome home is powered by solar energy, and the organic food garden and orchard are irrigated by creek water transported by a solar-powered water pump.

For more about Silvia’s inspiring story, go to www.generationtrees.com