Tackling the country’s smallest introduced rodent is essential to protect nature. By Chelsea McGaw

Wildlife will flourish once again if we eradicate possums, mustelids, and rats from Aotearoa, according to Predator Free 2050, the Crown owned company tasked with delivering this ambitious goal.

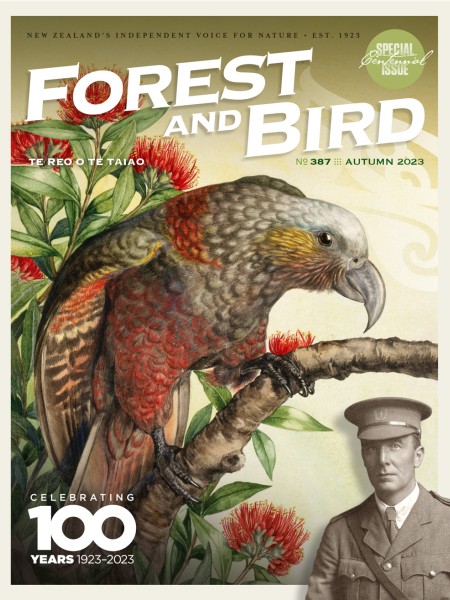

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Autumn 2023 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

However, there is a furry roadblock in the way – the house mouse (Mus musculus). This small rodent can have a devastating impact on New Zealand nature but is not currently on PF2050’s species list for eradication.

Mice may look harmless, but they predate on birds’ eggs and can kill a seabird chick several times larger than themselves, as a Birdlife team working on the Mouse-free Marion Island project in the sub-Antarctic Indian Ocean discovered in 2015.

They documented mice eating the rumps and heads of defenceless seabird chicks while they were still alive. It could take up to four days for chicks on the island to die.

House mice are omnivorous and are known to take advantage of whatever food sources become available to them, including invertebrates and lizards.

A study on the impact of mice on lizards at Mana Island, published by Donald Newman in 1994, showed that more than 20% of a mouse’s diet per month can be made up of native skinks.

When millions of mice were removed from Mana Island during 1989–91, in a project led by Forest & Bird stalwart the late Colin Ryder, populations of McGregor’s skink, the common gecko, and the Cook Strait giant wētā “increased significantly”.

These grey-headed albatross chicks did not survive the gruesome "scalping" inflicted by Marion Island's mice. Image Ben Dilley

Forest & Bird’s Tautuku Ecological Restoration Project manager Francesca Cunninghame says many threatened forest geckos found in the project’s area have missing digits on their feet and regrown tails.

“We believe these are the result of predator attacks from mice as the geckos jam themselves deep into crevices to try and get away, leaving only limbs exposed,” she said.

“But controlling mice in unfenced mainland areas such as Tautuku is currently an impossible challenge.”

Mice can also reduce the abundance of ground-dwelling insects, according to a five-year study published last year by Corinne Watts et al.

The team compared the abundance of ground-dwelling insects in forest blocks with relatively high and low numbers of mice at Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari, Waikato.

“We found strong evidence that mice reduced the abundance of ground-dwelling invertebrates, in particular caterpillars, spiders, wētā, and beetles, and reduced the mean body size of some taxa, the report concluded.

“Overall, there is substantial biodiversity gain from eradicating the full suite of pest mammals.

“We expect that mouse control tools will steadily improve so that in the future mice can be eradicated and excluded from forest reserves such as Maungatautari.”

But mice are not currently a priority for eradication. The government’s PF2050 efforts are focused on possums, stoats, ferrets, weasels, and Norway and ship rats.

The trouble is that once these dominant predators are removed, mouse populations can explode. A 2012 study at Tāwharanui Sanctuary north of Auckland found mouse densities were significantly higher after the

exclusion of mustelids.

Some experts suggest we should deal with mice first as they are the food source of higher-ranking predators. Rats eat mice and hibernating hedgehogs, mustelids eat rats and mice, cats eat everything.

Internationally respected New Zealand ecologist Dr John Flux says: “Ecology teaches us we should remove mice first, then get rid of rats, weasels, stoats, ferrets, and cats in that order.” Forest & Bird’s view is that pest management is most effective when it employs a long-term, landscape-scale strategy as well as targeting individual species.

“Unless the full suite of predators, including mice, are targeted, our native birds, reptiles, and insects are in real trouble,” says Nicky Snoyink, of Forest & Bird’s pest free campaign team.

McCann's skinks killed by mice. Image Marieke Lettink

Forest & Bird is having ongoing discussions with Predator Free 2050 and will be asking them to consider including all introduced predators to ensure our wildlife

truly does flourish.

Herpetologist Marieke Lettink has seen first-hand what mice do to native skinks caught in monitoring traps. She would like to see mice added to the PF2050 list

for eradication.

“Unfortunately, we don’t yet have the tools to effectively control mice at landscape scale.,” she said. “Coming from a herpetologist’s perspective, I see mouse control as the final frontier in pest control in New Zealand.”

Mousey mountain to climb

Forest & Bird's fairy prion fence, Dunedin. Image Kirk Serpes

Forest & Bird’s frontline conservation projects face an uphill battle when it comes to controlling mice and protecting threatened birds, lizards,

and insects.

On the steep cliffs of St Clair, Dunedin, mouse disturbance is thought to be stopping tītī Wainui fairy prions laying eggs despite the fenced area

being regularly controlled with toxin.

Last winter, project volunteers Graeme Loh and Sue Maturin built an experimental mouseproof nest box table to see whether it would encourage the birds to breed there this summer.

Meanwhile, at Bushy Park Tarapuruhi, a fenced sanctuary near Whanganui, Forest & Bird’s manager Mandy Brooke is constantly on

mouse watch.

She uses tracking tunnels and mouse-detecting dogs to identify an incursion and bait stations to knock them back to almost zero. Other fenced sanctuaries do the same.

At Tautuku, it’s thought that mice may be targeting the nests of titipounamu rifleman and the team is employing trail cameras to see if the rodents are visiting.