Managing Oparara’s fragile landscape is a balancing act, as visitor numbers threaten the very thing that makes it special – its wildness. Words and images by Neil Silverwood

Visiting the Oparara Basin, in Kahurangi National Park, gives visitors an opportunity to step back in time and glimpse an ancient landscape with spectacular limestone caves and arches, and primeval rain forest, which is almost unchanged from when humans arrived in New Zealand. If visitors are lucky, they may spot some of the local residents including whio, weka, kākā, great-spotted kiwi, and Spelungula cavernicola, New Zealand’s only protected spider.

The Oparara River, the colour of strong tea, meanders peacefully through the centre of the basin in and out of the caves and limestone arches. As well as walkers, cavers, and nature lovers, paleontologists also come here to study in-situ subfossil deposits, including moa and Haast’s eagle, which are perfectly preserved by the caves’ constant weather-less climate.

Photo Credit - Neil Silverwood

Some of the most dramatic landscapes in New Zealand are karst – from Castle Hill rocks, near Christchurch, to the iconic subterranean wonders of Waitomo. While karst features make up some of our most amazing and memorable landscapes, only 3% of New Zealand’s landscape is karst, compared to a continental average of 14% around the world.

In Aotearoa, about two-thirds of our rare karst landscapes have been heavily modified through logging, quarrying, agriculture, and tourism. However, the Oparara Basin remains pristine, albeit fragile.

But it’s a fragile landscape under pressure from increasing numbers of tourists. Cave formations crumble from the slightest touch, whio nest right next to a busy visitors’ car park, and Spelungulas are increasingly being exposed to light pollution from torches worn by visitors eager to see New Zealand’s largest and rarest spider.

Tourist numbers on the West Coast have increased markedly in recent years, principally from the nationwide increase in tourist numbers but also from the Kaikōura road closures after the earthquake. Many conservationists feel Oparara is already at full capacity, which is why there is widespread concern about plans being drawn up to “develop” it into a prime tourist destination.

Suggestions out for consultation currently include a suspended platform in the main arch, new walks through some of the most pristine sections of the basin (which contain sensitive caves), private accommodation within the national park, and commercial ventures – even opera has been suggested.

I recently spent several days in the Oparara Basin working on a photo essay highlighting the fragility of the karst landscape. It’s been claimed that “development” is needed because tourists are having a negative experience at Oparara, but I spoke to many visitors and almost all had come to get off the beaten track and escape places such as Punakaiki, where tourist numbers have grown to a point that it negatively impacts on the visitor experience. They were there to escape concrete pathways, crowded viewing platforms, and tacky tourist shops, and every single one rated the Oparara experience highly.

Photo credit - Neil Silverwood.

About 870,000 tourists visited the West Coast in 2016, and West Coast Tourism has set a goal of attracting 1.1 million people by 2021. This isn’t the first time Oparara has been under threat. It was here that the logging stopped in the 1980s after a clash between environmentalists and local Karamea residents wanting to log the sprawling podocarp forests in the basin. In 2016, the Department of Conservation commissioned the Lincoln University Landscape Design Lab to come up with some ideas for developing the Oparara Basin. Funded by the Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment, the report recommended, among other things, a “sound and light” immersive experience that gave little consideration to the fragility of the area and its caves.

Thankfully, this idea was abandoned, and DOC handed over the project to Tourism West Coast to come up with alternative ideas. This led to Tourism Recreation Conservation, an international tourism and planning consulting firm based in Australia and New Zealand, conducting research and releasing a draft concept paper in May this year. The paper, which was commissioned with joint funding from MBIE/Development West Coast, outlines ideas for how Oparara can be “developed” and suggests there is potential for significantly more tourists – up to a three-fold increase.

Once again, the plans, backed by the tourism industry and private business, give little consideration to conservation issues – or the legal protections afforded by the Conservation Act and the National Parks Act. The Kahurangi National Park Plan states one of its primary objectives is to “retain the essential character of Kahurangi National Park as a remote, undeveloped, natural area of great beauty, natural quiet and diversity, and of value for whakapapa, recreation, appreciation and study.” It’s hard to see how this Oparara plan aligns with this goal.

The main rationale for development of the Oparara is to draw tourists north through Westport and Karamea. But how would the new track network, and a significant increase in visitor numbers, upset the delicate balance in the basin? No environmental assessment of the impacts has been undertaken – usually a first step before even considering a development like this. This case also sets a precedent by allowing the tourism industry to have a strong voice when it comes to the management of our wild places.

DOC has previously justified the potential developments at Oparara by claiming tourists are not having a good experience there, the tracks need to be upgraded to provide easier access to the arches, and the road to Oparara is unsafe.

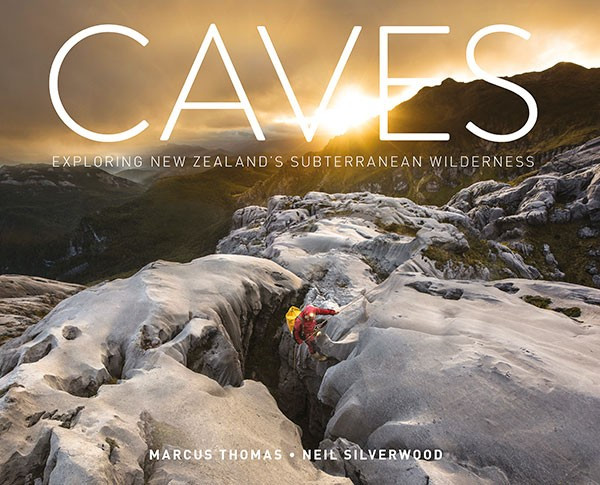

Contributor Neil Silverwood’s Caves book has just scooped the Judith Binney best first book award. To celebrate, Potton & Burton is offering Forest & Bird readers 10% off and free delivery. Order online at www.pottonandburton.co.nz and use the discount code CAVES18. Offer expires 31 August 2018.

Ironically, increased car numbers on the road are in part largely the result of Tourism West Coast’s advertising campaign to get more tourists to venture there. Last year, there were 47 minor road accidents on the Oparara road.

Two solutions, yet to be seriously considered, include closing the road during summer and offering a shuttle service, or shortening the road and having a longer walk into the basin. Both would help control visitor numbers, make the drive in safer, and help protect the Oparara’s natural values. Collectively, we need a conversation about how to manage the Oparara Basin that focuses on its preservation.

We need to protect the small amount of unmodified karst we have left in New Zealand. DOC needs to step forward and take a leadership role supporting the conservation of this pristine and fragile landscape – rather than enabling businesses that want to exploit it for economic gain.

*A version of this story first appeared in the Winter issue of Forest & Bird magazine, join today at www.forestandbird.org.nz to receive your copy. Membership costs from $57 a year and includes a free annual subscription to Forest & Bird magazine.