Researchers have been unlocking the incredible carbon-capturing qualities of New Zealand’s largest peat bog. By Zoe Brown

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Autumn 2022 issue of Forest & Bird magazine

On the Hauraki Plains, around 40km northeast of Hamilton City, lies a vast expanse of waterlogged wilderness. Wedged between the Piako and Waitoa Rivers, this outlandish yet oddly enchanting habitat is Kopuatai Peat Dome: the largest remaining unaltered raised peat bog in Aotearoa.

Remarkably, despite stretching a hefty 10,201ha, many people are unaware of Kopuatai’s existence. Even local farmers who work on the many neighbouring dairy or blueberry farms may not know about this Ramsar wetland of global significance.

Others, however, are no strangers to the area. Waikato University ecohydrologist and wetland expert Dr Dave Campbell has been conducting hydrology and carbon research in and around Kopuatai, and the wider Waikato region, for more than two decades.

“A lot of people live in the lower Hauraki Plains near this amazing 100km2 area of wilderness, yet there really is no public access. I’d love to see that change so more people can experience the wonders of Kopuatai,” says Dave.

Part of Kopuatai’s quiet appeal is that it is home to an array of unique wetland species.

Hidden from public view, except from the air, is another important feature – a small research tower bedecked with many specialised monitoring instruments. This tower, in the heart of the peat bog, is the centre of operations for Dave’s fieldwork, studying the carbon-capturing abilities of the wetland.

The upward-growing cluster roots of Empodisma robustum forms the bulk of peat. This cross-section grew over a 10-year period. Credit: Dave Campbell, University of Waikato

Peat bogs are formed in low-nutrient, water-logged areas where an absence of oxygen and microbial activity in the soil means dead vegetation only partially breaks down. The result is a slow but steady accumulation of semi-decomposed plant matter, deep brown in colour – and exceedingly rich in carbon.

Currently, New Zealand’s emissions-reduction plans favour the use of forestry to capture and hold carbon. However, Dave’s research suggests that wetlands are a better alternative.

“A mature pine forest holds 300 tonnes of carbon per hectare while Kopuatai holds 2400 tonnes of carbon per hectare,” explains Dave.

He points out that this carbon has accumulated over thousands of years. But forests, unlike peatlands, cannot continue to accumulate more carbon indefinitely. They reach an old-growth stage, wherein they either burn and release their stored carbon as CO2 or else uptake simply plateaus.

By way of contrast, a peatland like Kopuatai is in a constant state of slow but steady carbon uptake.

“It’s a classic case of the tortoise versus the hare. It’s slow to accumulate, but, in the end, it will travel 10 times further than the hare ever will,” Dave adds.

Crucially, this carbon storage ability only persists as long as the wetlands remain wet.

Sadly, over the past 160 years, around 75% of Waikato’s wetland areas – and 90% of all wetlands across Aotearoa – have been drained and converted to farmland. Draining peatlands introduces oxygen back into the soil, turning these highly efficient carbon sinks into a major source of carbon.

Since 2011, Dave’s team has been continuously monitoring CO2 exchange between the soil, plants, and the air above Kopuatai and on drained peatlands used for farming. This allows Dave to compare the carbon gains and losses from an intact wetland versus the drained equivalent.

Dr Dave Campbell with a peat core. Credit: Veronika Meduna

His research has revealed that a single hectare of drained peatlands will emit up to 30 tonnes of CO2 per year.

“It’s likely that emissions from drained organic soils, predominantly peatlands, could account for around 8% of New Zealand’s entire greenhouse gas emissions. So it’s not just a few percentage points. It’s really quite major,” he points out.

Over the past two decades of research, Dave has gained vital insights into Kopuatai, not least of which is the extraordinary resilience of the bog to drought.

Indeed, possibly the most unique and remarkable attribute of the raised peat dome at Kopuatai is the very fact that it exists at all.

In the Northern Hemisphere, deep peatlands form in areas where the cold, rainy climate and short growing season lends itself perfectly to waterlogged soils, limited plant decomposition, and therefore a build-up of organic matter.

Think Ireland, Siberia, and the Scottish Highlands. But a peat bog in sub-tropical northern Aotearoa?

“Northland and Waikato are the antithesis of the parts of the world where you’d expect to accumulate deep peatlands, because this is a warm, seasonally dry climate,” says Dave. “They simply should not exist.”

So how did Kopuatai come about?

“It’s all in the plants. They are the intersection between the Earth’s water and carbon cycles,” explains Dave.

Jointed wire rush. Credit: Dave Campbell

“Wetland plants like Empodisma robustum – jointed wire rush – have particular adaptations that enable them to hold onto the water they get from rainfall. This indicates they are equipped to withstand the effect of seasonal droughts.

“The big lesson we’ve learned is how resilient these particular peatlands are to a fluctuating climate. That is globally unique, and it gives us hope that they’ll be very resilient to climate change.”

This is not to suggest that a peat wetland is completely insensitive to the dangers posed by a changing climate.

Fire risk, for instance, remains a threat, as we have seen in the tragedy unfolding in Kaimaumau in the Far North, where a long-burning fire has resulted in the loss of endangered flora, fauna, and sacred Māori sites.

Carbon storage represents just one of many ways in which wetlands contribute to maintaining a stable environment. For example, places such as Kopuatai also act as filters, helping to ensure supplies of clean, fresh water.

Protecting and restoring wetlands means people benefit from all the services they provide, including reducing carbon emissions and protecting our endangered flora and fauna.

“I tend to advocate wetland restoration for multiple benefits. It’s about water quality, biodiversity, and it’s a major carbon sink that is perhaps more resilient than standard pine forests,” says Dave.

Together with colleagues at Manaaki Whenua Landcare research, Dave is looking at developing tools to help farmers and others restore peat wetland back to carbon-sequestering vegetation.

Purple bloom of the striped sun orchid Thelmitra cyanea.

Kopuatai is currently jointly managed by DOC and the local iwi, Ngati Hako. They, as well as Dave, believe a crucial first step in encouraging the government and landowners to look after and restore our precious peat bogs is to draw attention to the value of special places like Kopuatai and Kaimaumau.

“If you don’t value an ecosystem, you’re not incentivised to look after it. It’s really important that people understand just how special these places are.”

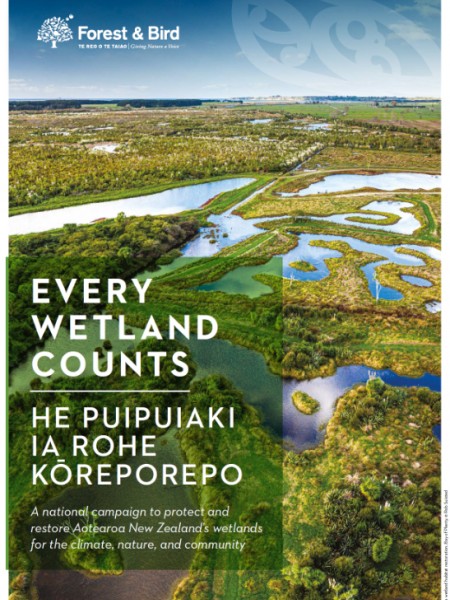

Every wetland counts

Image credit: Rob Suisted

Our new report explains how wetlands help the climate, community, and biodiversity and sets out six actions the government needs to take to reduce the effects of global warming. First on the list is doubling the number of natural wetlands by 2050!

Read more about our Every Wetland Counts campaign.

Download a copy of our wetlands report.

If you haven't already, please sign our petition.