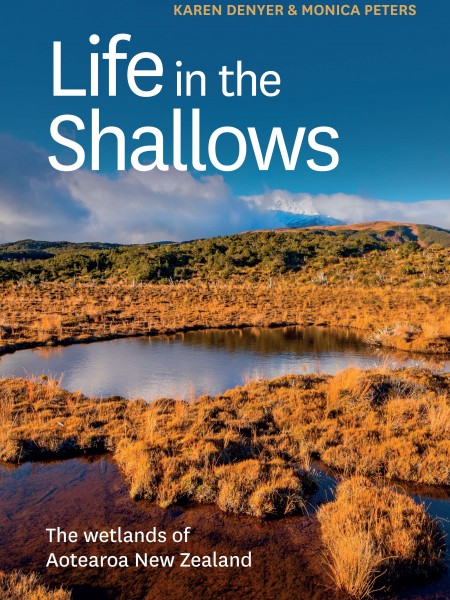

A Q&A with wetland experts Karen Denyer and Monica Peters, who recently published Life in the Shallows, a new book celebrating the “ecological underdogs” of the natural world.

Why wetlands?

Karen Denyer, author. Credit Craig Cook

Karen Denyer: I’ve always had a soft spot for the underdog, and for me wetlands are our ecological underdogs, our most abused and misunderstood ecosystem. Western culture still “body shames” wetlands, using wetland terms like swamp and bog in a negative way and allows commercial catch of threatened fish species. Imagine the uproar if kiwi were able to be legally caught, killed, and turned into fritters or dog food! We’ve saved a third of our native forests and legally protected 80% of them but destroyed 90% of our wetlands and only protected half of the tiny amount left. So, to me, they are an ecosystem that just needs a bit more love and attention.

Monica Peters, author. Image supplied

Monica Peters: They’re intriguing places — it’s not just the glimpses of open water, but the damp swathes that are home to plants that couldn’t survive without “wet feet” either seasonally or year-round. As a plant geek, that’s my first focus, but I’ve also begun to appreciate our unique fauna that need wetlands for their survival — the birds, fish, and insects.

What has been your most exciting wetland moment?

MP: Visiting Kopuatai Peat Dome in the middle of Hauraki Plains and the surreal experience of standing on a ladder among the mighty tufts of Sporadanthus ferrugineus (giant cane rush) and feeling as if the wetland covered the whole landscape. It was ferociously hot (40°C!), which really surprised me, and the plants were, quite simply, otherworldly.

This book profiles the personal stories of 17 leading wetland scientists. Why did you decide on this approach?

KD: New Zealand is great at idolising our talented athletes, but many of our academic heroes — who also put Aotearoa on the map — get very little attention at home. We thought, let’s write a book not just about wetlands but about wetland scientists. We write about some of their hairy field moments, their lateral thinking, and the social obstacles they overcame.

Dr Don Jellyman with longfin eel, Selwyn River, Canterbury. Credit NIWA

You profile special kōreporepo in your book. Do you have a favourite wetland?

KD: That’s a toughie; they are all so different. Geothermal wetlands are incredible, and I love the tiny detail of minute orchids, sundews, and mosses in peat bogs, but one place that I come back to is Kaitoke on Aotea Great Barrier Island. Because it’s right beside the airport, you fly low over it, and I usually have my nose pressed against the window picking out the various plant species.

MP: Tahuna Torea in Auckland. It’s a spit of sand that arcs into the Tāmaki Estuary, with wetland areas restored over the decades. It’s just down the road from where I grew up. I went there a lot, loving the solitude and how the tides grew and diminished the shoreline, and filled and emptied the shallow pools within the wetland.

Parts of the book talk about mātauranga Māori. What does this traditional knowledge bring to the study and restoration of wetlands?

KD: Western scientists have had barely 200 years to learn about New Zealand wetlands, and most of them have been limited to researching a fraction of the wetlands that once existed, many now degraded and with half their species gone. It is like doing a jigsaw with no box cover and only 10% of the pieces. Māori have lived in and beside wetlands for more than 800 years and had the full picture. They have so much intimate knowledge and experience of wetlands: how they work, how they changed seasonally, and how they once were. They observed and interacted with species that are now extinct. It has become clear to most scientists — Māori and non-Māori — that, to fully understand a natural area, it makes sense to first talk to local iwi and find out what they know from oral history and their own observations. Blending traditional knowledge with Western science dramatically increases our understanding. For instance, learning where and when fish species that are now rare were once harvested can help us locate and protect spawning sites or migration pathways.

MP: Mātauranga Māori brings a dimension that has been missing for a long time, with predominantly Pākehā scientists and land managers leading wetland initiatives. Restoring our degraded landscapes isn’t just about an ecological fix, it’s situating restoration actions into a wider socio-cultural context.

Dr Emma Williams with a bittern and conservation dog Kimi. Credit Colin O’Donnell

Life in the Shallows by Karen Denyer and Monica Peters is published by Massey University Press, RRP $65. All royalties will go to the National Wetland Trust to further its advocacy work.

Win a book

Life in the Shallows is a timely engaging guide to New Zealand’s wetland habitats and the people who study them. Home to unique flora and fauna, wetlands sequester more carbon than our forests and can help mitigate some of the worst effects of extreme weather events. But they remain underappreciated. This richly illustrated book brings our wetlands out of the shallows and into the limelight. The authors include a detailed guide to 17 wetlands, including how to get there and their ecological highlights.

We have two copies to give away. To be in to win, email your entry to draw@forestandbird.org.nz, put SHALLOWS in the subject line, and include your name and address in the email. Or write your name and address on the back of an envelope and post to SHALLOWS draw, Forest & Bird, PO BOX 631, Wellington 6140.

Entries close 1 November 2022.