It is our good fortune and legacy to have both Māori and scientific names to describe the natural world around us. By Ann Graeme

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the winter 2021 issue of Forest & Bird magazine

In our native forest grows a moss, the largest moss in the world. Most pākehā simply call it the “giant moss”.

That is not very original.

Scientists have named it Dawsonia superba.

“Superb” is quite eloquent for a scientific name, and “Dawson” is a tribute to Dawson Turner, a distinguished British botanist and moss expert.

That is mildly interesting.

Māori called this moss pāhau kākāpō – “the beard of the kakapo”.

Now that is a name to remember!

What’s in a name? Quite simply, everything. Names provide identity, which is essential for communicating in a society. Scientific names, unique and universal in their usage, are vital for international scientific communication.

Names in te reo were equally vital in Māori society. Pre-European Māori looked at nature in a different way to modern scientists. They had an intimate knowledge of the natural world. They created practical, descriptive names that identified their sources of food, clothing, shelter, medicine, tools, and weapons. They created evocative, imaginative names because nature was the fount of their stories and understanding of the world.

The name pāhau kākāpō is both a playful image and a clever observation, comparing the little spiky leaves of the moss with the green, hair-like feathers that surround the kākāpō’s face.

PARATANIWHA

Parataniwha leaves feel like sharkskin. Credit Auckland Zoo

The plant parataniwha belongs to the nettle family and has lush, frond-like leaves, often pink with new growth. Its name can refer to its rough leaves, which feel like sharkskin, for the shark was considered a taniwha.

As parataniwha grows in dark, damp places in the forest, often in overhangs behind waterfalls where monsters might well dwell, its name can also mean the home of the taniwha, or water monster.

WĒTĀPUNGA

Wētāpunga are the giants of the underworld. Credit Jake Osborne

Foraging in the forest, Māori would often have encountered the large insects known to all of us.

Wētā are a specialty of Aotearoa. There are about a 100 species, and they lived everywhere, including in trees (pūtangatanga, tree wētā) or in dark places (tokoriro, cave wētā).

Together, they used to play roles similar to rats and mice in other countries, eating vegetation and small invertebrates, and spreading seeds in their droppings.

But when actual mice and rats arrived, they took over the wētā niches and ate the wētā themselves. So, despite their spiky legs and ferocious faces, many wētā are now endangered, and none more so than the giant of them all, which Māori called wētāpunga.

This means “God of ugly things”, and ugly they are.

Scientists too were struck by its scary appearance and named its genus Deinacrida, Greek for terrible or devil. The tragic irony is that giant wētā are not aggressive (except to other male giant wētā) and are very unlikely to bite you. They cannot fend off a rat or cat or hedgehog, so all giant species are endangered, and most only survive on pest-free islands.

PUTAPUTAWĒTĀ

Putaputawētā or the marble leaf tree is home to puriri moths and wētā. Credit Jon Sullivan CC Flickr

While you won’t meet a giant wētā in your garden, you may meet a tree wētā if you have a marble leaf tree known as putaputawētā to Māori.

It is often host to the puriri moth, whose caterpillar tunnels through the tree trunk before pupating and emerging as an adult moth. The empty hole then offers an ideal home for wētā, hence the tree’s name putaputawētā, which means lots of holes and wētā.

AKEAKE

Akeake is a strong hardy coastal tree. Credit University of Auckland

Wood was the building material of Māori. They knew the attributes of different timbers, their strength, their hardness, and their usefulness in carving. The coastal tree, akeake, is named for its exceptionally hard wood, which was used for making weapons.

Ake ake means “forever” or “everlasting” in te reo. In World War II, the 28th Māori Battalion marched into Greece, Crete, North Africa, and Italy singing “Ake! Ake! Kia Kaha e!”, meaning “for ever and ever be strong!”.

RIRORIRO

Riroriro “serenader of spring”. Credit Craig McKenzie

Just as the trees define the native forest, so too do the native birds. Māori knew them all, and their knowledge is reflected in the names they gave and the stories they wove around them. When the riroriro or grey warbler sang in Spring, Māori knew it was time to begin planting crops.

This whakataukī or Māori proverb mirrors a European children’s story, “The Little Red Hen”, about a lazy person who won’t help but later wants to share the harvest. I whea koe i te tangihanga o te riroriro, ka mahi kai māu? Where were you when the riroriro was singing, that you didn’t work to get yourself food?

TAUHOU

Tauhou “the stranger”. Credit Oscar Thomas

Māori knew and named all the native forest birds, but, when European immigrants began arriving, a new bird arrived with them – the Australian silvereye.

Sometimes, these tiny birds are blown out to sea in westerly storms, but few, if any, survive the 1500km flight to our shores. But, in the 1850s, some passengers recorded exhausted silvereyes clinging to the ships’ riggings and crouching on the decks.

Enough birds arrived in Auckland to begin breeding, and soon silvereyes spread throughout Aotearoa.

Today, they are one of our most abundant garden birds. Silvereyes were a new bird for Māori, and they gave them an appropriate name. They called them “tauhou”, which means “the stranger”.

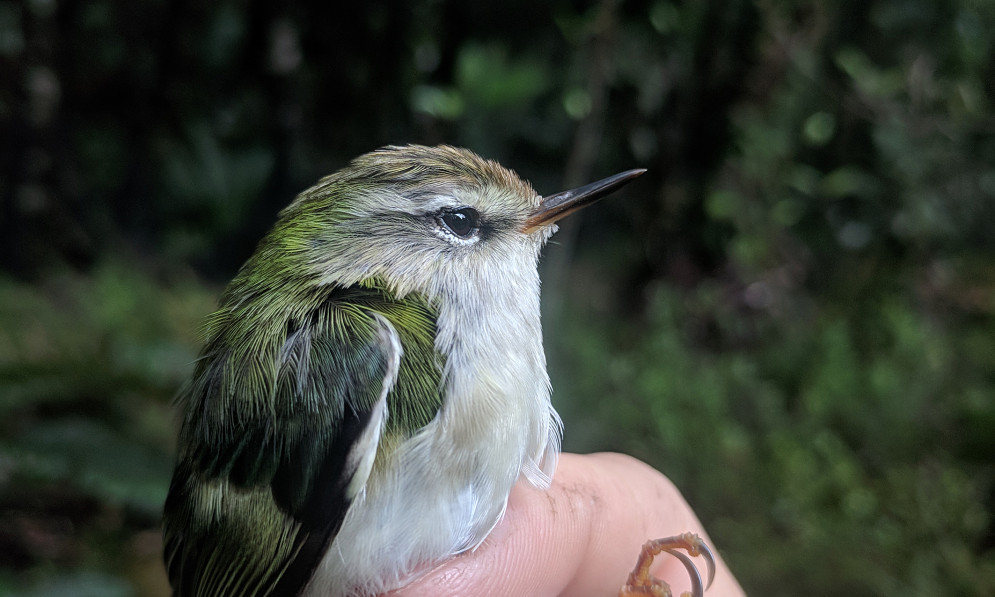

TĪTIPOUNAMU

Tītipounamu “squeaky voice”. Credit University of Auckland

If tauhou is a newcomer, the rifleman is a species with an ancient lineage in Aotearoa. Its Māori name tītipounamu is beautiful. It combines “tititi”, its squeaky call, with pounamu or greenstone, after the bright green feathers of the male rifleman.

TŪTAE KĒHUA

Tūtae kēhua “poo of a ghost”.Credit Bernard Spragg

Not everything in nature lends itself easily to describing and understanding. What could tangata whenua make of the grotesque and smelly structure that seems to emerge spontaneously from the earth? Its common and prosaic Pākehā name is basket fungus.

Māori used much more imaginative kupu to describe it. They called it tūtae kēhua, which means “the poo of a ghost”!

Every society has created names to help them understand and describe the world around them. We use names from around the world, like the pretty blue garden flower from Europe called love-in-a-mist. But Māori names are unique to Aotearoa.

Scientists all over the world can understand Dawsonia superba, but few will know it as pāhau kākāpō. The scientific name gives us one dimension. Pāhau kākāpō gives us another, a visual and of-its-place picture of a plant that the Latin name can never provide. It is our good fortune and our legacy to have them both.

The many iwi of Aotearoa often had different kupu and different interpretations of words, to identify the world they lived in. That is why you find variation in the Māori names for animals and plants. This article is about some of the names and stories, and is neither exclusive nor comprehensive.

Thank you to Robert McGown for his assistance.