Old podocarp forest stands alongside rare native plant collections cared for by gardeners, conservation scientists, and community volunteers at Wellington’s Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush. By Kathy Ombler

Forest & Bird magazine

A version of this story was first published in the Autumn 2024 issue of Forest & Bird magazine.

It’s dusk. Kākā screech around an old hīnau tree, epiphytes dripping from its upper branches. Nearby is a subtropical Manawatāwhi kaikōmako, from the Three Kings Islands, grown from a cutting taken in 1945 from the last tree left of the species.

Turn around and you’ll see a 1000-year-old northern rātā, while just down the path stands a smaller rātā moehau. Only 13 of these white-flowering trees remain in the wild. A spiky taramea speargrass lurks beside the tarn of a native alpine garden.

A number 14 city bus pulls up, its stop just 5km from the Wellington CBD. Welcome to Ōtari Native Botanic Garden and Wilton’s Bush Reserve, known more simply as Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush and officially recognised as a six-star garden of international significance.

How can it be that such old forest, botanical rarities, and sub-alpine plants exist in our capital city? The answer, essentially, is foresight.

In the 1860s, much of the land at Ōtari was cleared for farming, but one forward-thinking settler, Job Wilton, recognised the value of the lowland podocarp forest and fenced off 7ha of the land for its protection.

He also welcomed the public to visit, and weekend picnics at Wilton’s Bush became quite the thing for Wellington families and church groups. A gently graded dray road, built by Wilton for access to his farm, today forms one of Ōtari’s most popular walking tracks.

As a settler/farmer, Wilton was perhaps a man ahead of his time. Later, when farming stopped and adjoining land was reserved, his unfelled forest became the best possible seed nursery, allowing rapid natural regeneration in the valley.

Fifty years on, another visionary, botanist Leonard Cockayne, one of Forest & Bird’s founder members, expressed alarm at the pace with which New Zealand’s native vegetation was being destroyed.

With support from Wellington’s Director of Parks and Reserves, J G MacKenzie, and promotion by the Royal NZ Institute of Horticulture, five acres at Ōtari were set aside for an “Open Air Native Plant Museum”, which officially opened in 1926.

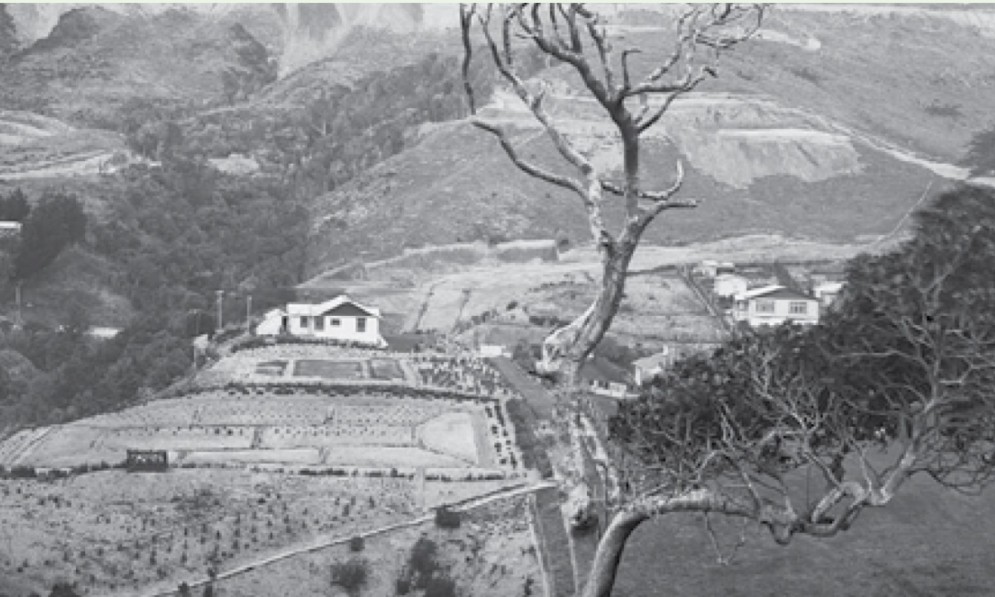

View of Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush 1932. Photographer unknown. Image Alexander Turnbull Library

Here, native plants gathered from around the country were planted in traditional taxonomic living collections, and Cockayne became one of the first to attempt to recreate ecosystems from around New Zealand that replicated the plants’ natural habitats.

Today, Ōtari is officially a botanic garden – in fact, the only public botanic garden in New Zealand dedicated to native plants. Around 1200 species, 340 of them threatened, from all around New Zealand and its offshore islands grow here.

Alongside stands Wilton’s Bush, now a 100ha reserve of mature native forest, most of it more than 100 years into regeneration, along with the original remnant forest protected by Wilton. Together, the forest and gardens combine to make one grand interdependent nature experience.

Cockayne’s four-point vision for Ōtari was to grow as many native species as possible, demonstrate New Zealand’s many different plant communities, show how native species could be worthy garden plants, and restore the adjoining native forest to its natural state.

Almost a hundred years on, aided by a succession of similarly motivated curators each adding their own enhancements – Walter Brockie’s Rock Garden, Ray Mole’s Fernery, Mike Oates’ Canopy Walkway and Alpine Garden, Rewi Elliot’s 38 Degrees Garden, and current manager Tim Park’s Rēkohu and Epiphytes Gardens – Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush continues to evolve, always inspired by Cockayne’s vision.

The place is also incredibly popular, not only for learned botanists and scientists. Families, friends, walkers, runners, garden clubs, students, kairaranga (weavers), photographers, locals, and visitors all regularly enjoy the garden collections, the forest tracks, the picnic and barbecue lawns, the birdlife, and spotting tuna in the Kaiwharawhara Stream.

And let’s not forget the volunteers: from retired botanists to keen locals to teenage trappers, there is huge community commitment to support and enable what is happening here.

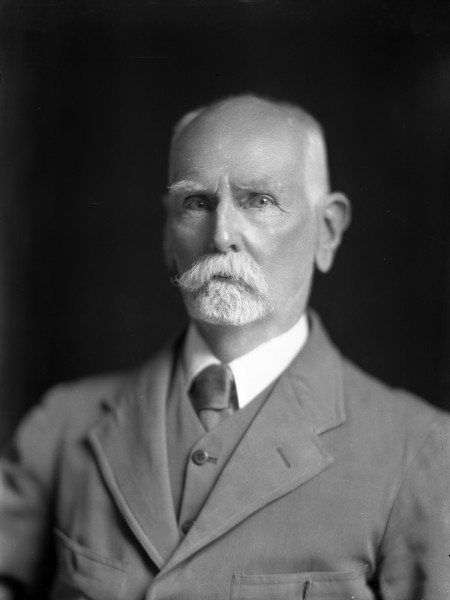

Tim Park

“Our gardening staff simply couldn’t do what we do without our wonderful volunteers,” says Ōtari Manager Tim Park. “They also bring a spark of energy due to their love of the place. This really encourages our determination to inspire people with our native plants.”

Bringing people and plants together and building relationships with mana whenua will be Tim’s ongoing focus for Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush. He says the new Rēkohu Garden, showcasing plants from the Chatham Islands, is an example of this.

“Moriori have shared their knowledge. Now, we are using this to tell the story of the evolution of plants in New Zealand, with and without influence such as moa. Our staff have also contributed to restoration on Rēkohu, so we’ve built a two-way relationship.”

At last December’s opening of Ōtari’s Pā Harakeke, a collection of harakeke plants especially chosen and planted for weavers, Tim spoke with emotion about embracing the cultural use of plants.

Lily Yochay harvesting harakeke

“These plants are not curiosities. They are able to be used, and they are resources that can strengthen our cultural connections.”

Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush is managed by Wellington City Council. Staff include gardeners, plant conservation scientists and a plant collections archivist. They are a dedicated lot with specialist knowledge. Gardener Dave Bidgood, for example, has been at Ōtari for 25 years and developed a huge understanding of the specific nurturing required for the many rare native plants in Ōtari’s care.

Ōtari staff Dave Bidgood and Megan Ireland. Image Chris Coad

The Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush Trust was established in 2001 to support the council in its management of Ōtari.

“We provide huge assistance with our bevy of volunteers who help with the inevitable shortfall of labour,” says Trust chair and noted botanist Dr Carol West.

Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush. Image Chris Coad

“Trust volunteers have dedicated thousands of hours to forest restoration, weeding, replanting, garden maintenance, nursery propagation, predator control, guiding, and weekend hosting.

“Another key aim of the Trust is to promote awareness. We do this through hosting, guided walks, seminars, social media, and our book Ōtari: Two hundred years of Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush. The underpinning purpose of these activities is to educate people on the importance of our unique native flora.”

Advocacy is also a Trust focus. This year, it has been lobbying to keep a much-needed landscape redevelopment of the nursery and laboratory space in the city council’s long-term plan.

“I am very proud of what the Trust has achieved in 20 years,” says Carol. “Looking ahead, we are now poised to contribute even more significantly to native plant conservation, with the recent establishment of the Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush Fund.” The Fund was launched in partnership with the Nikau Foundation in February.

In all, a huge sense of community and care exists around Ōtari Wilton’s Bush. This was epitomised at the opening of Pā Harakeke, when staff, trustees, volunteers, locals, and weavers all came together, sang tautoko waiata, and helped with the first hauhake harvest. Some then joined a raranga weaving workshop in the Leonard Cockayne Centre, the former curator’s house, that looks over the plant collections, past the grave of Leonard Cockayne, to the forest beyond.

Entwining people, plants, culture, history, and conservation, it was Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush encapsulated.

Volunteer gardeners. Image Kathy Ombler

LEONARD COCKAYNE VISIONARY BOTANIST (1855–1934)

Cockayne is regarded as one of the country’s most influential scientists and prolific observers of New Zealand plants and vegetation.

For more than 30 years, he conducted botanical surveys throughout New Zealand, including the sub-Antarctic and Chatham Islands. His work was influential in the formation of Arthur’s Pass National Park and kauri protection in Waipoua Forest.

He was passionate about plant ecology, and many of his published works remain the standard accounts of New Zealand vegetation.

He was, said Kew Gardens director Sir Arthur Hill, “an ecologist waiting for the term to be adopted by botanists”. With Hill and other colleagues, he scoured the country, from mountains to offshore islands, collecting plants for observation and research at his beloved Ōtari.

It was indeed good fortune for Wellington that Cockayne settled there and realised his dream of creating a “museum” of native species. Cockayne and his wife Maude now rest in peace in Ōtari, their grave marked by a massive memorial stone overlooking the gardens and forest.

SIX STANDOUTS

Moko. Image Carol West

MOKO, RIMU, DACRYDIUM CUPRESSINUM

Wellingtonians love to visit Moko, Ōtari’s 800-year-old rimu, deemed so special it was bestowed a name by mana whenua. Like all the old-growth trees in Ōtari, Moko plays a vital role in the forest ecosystem, hosting epiphytes, including northern rātā and the rare kōhurangi Kirk’s daisy, locally extinct in Wellington until its recent return to Ōtari.

NGUTU KĀKĀ, KĀKĀBEAK, CLIANTHUS MAXIMUS

Ngutu kāka. Image Andy Arthur

It’s hard to miss the flashy red ngutu kākā in Ōtari in spring. Kākābeak cultivars are readily available from garden centres, but only a handful of plants remain in the wild. Ōtari’s ngutu kākā now come from Tairāwhiti, gifted by Graeme Atkins of Ngāti Porou, as the seedlings were destined to be grazed to death by deer and goats in the wild.

Manawatāwhi kaikōmako. Image Kathy Ombler

MANAWATĀWHI KAIKŌMAKO, PENNANTIA BAYLISIANA

The unique flora of Manawatāwhi Three Kings Islands evolved in semi-tropical isolation, but goats, released in 1899 to provide food for castaways, decimated the vegetation. In 1945, a visiting botanist found just one manawatāwhi kaikōmako, growing on a cliff where the goats couldn’t reach. It was described then as the world’s rarest tree. The botanist retrieved cuttings, and one came to Ōtari, where the tree now flourishes. More of the species have subsequently been planted at Ōtari.

RĀTĀ MOEHAU, BARTLETT’S RĀTĀ, METROSIDEROS BARTLETTII

Bartlett’s rātā, rātā moehau. Image Carlos Lehnebach

This white-flowering tree rātā was known to northern iwi Ngāti Kuri but only “discovered” by botanist John Bartlett in 1975. Just 13 plants remain in the wild, near Spirits Bay. Two established rātā moehau trees grow in Ōtari, and the new “rātā shrine” structure hosts a young rātā moehau in the Epiphyte Garden. Ōtari staff are working to support Ngāti Kuri kaitiaki by cross-pollinating flowering cuttings taken from the few remaining plants in the wild to help the species recover.

KŌHURANGI, KIRK’S DAISY, BRACHYGLOTTIS KIRKII VAR. KIRKII

Kirk’s daisy. Image Kathy Ombler

Usually an epiphyte but also grows as a small shrub, this threatened white daisy is highly palatable to introduced mammals and was extinct in Wellington city. Plants collected from Wellington regional parks now flourish as both epiphytes on Moko and other old trees and as a shrub in the garden collections.

NORTHERN RĀTĀ, METROSIDEROS ROBUSTA

Northern rātā. Image Kathy Ombler

Wellington’s northern rātā forests were cleared for farming, felled for building, and subsequently ravaged by possums. But, thanks to Job Wilton’s protection and later intensive possum control, the city’s only old-growth northern rātā forest survives in Ōtari. Some may be more than 1000 years old, and the tallest are more than 30m high.

⏎