An inspiring initiative led by Māori and supported by Forest & Bird could create a way forward to protect marine life. By Dean Baigent-Mercer.

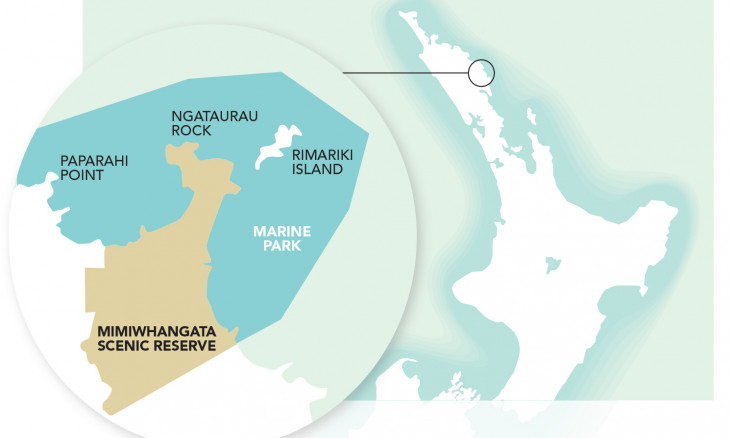

Mimiwhangata is an arm of land between the Bay of Islands and Whāngārei that reaches towards the Poor Knights Islands. It’s surrounded by small islands, sandy beaches and rocky reefs. Decades of attempts to protect this special marine area have so far failed and the degradation of sea life has continued. But the huge potential for recovery has inspired Forest & Bird’s continued support for aspirations of local hapū towards marine protection that could have benefits at Mimiwhangata and around the country.

Kaumātua Puke Haika, 73, remembers the old ways. “I’ve been brought up in a community of conserving resources. My grandparents and father organised their seafood gathering beginning at Whitikau, right down to Rimariki [roughly 23 kilometres of coastline]. It would probably take them the best part of 20 years to get there and the diving places you’d go back to once every 10 years. They would never go back until they reached the south end of their gathering place. That’s how they used to do it when I was a young fella.”

The initial wave of depletion and overfishing came from commercial fishing boats in the 1950s and “they got real heavy out here in the 60s and 70s”, recalls Uncle Puke. “Around the mid-80s we noticed big changes in the stocks.”

In 1984, in an effort to put brakes on the damage, a marine park was declared off Mimiwhangata. Dr Roger Grace has monitored Mimiwhangata and similar sites at Tawharanui, north of Auckland, since 1976.

“At Tawharanui nobody has taken crays for 29 years. Mimiwhangata became a marine park in 1984. The rules at that time still allowed commercial fishing for snapper and potting for crayfish, with a 10-year phase-out. So from 1994 there was no commercial fishing for crayfish at Mimiwhangata. In

1984, the rules for the marine park changed – no sinkers allowed, one hook per line and you couldn’t use nets. Recreational fishers could use one craypot, no more.

“But it’s gone slowly downhill from an area that was fished down already.”

Kina barrens are areas of very low diversity. Kina have overpopulated the area and eaten all of the kelp. Kelp is like the rainforest of the sea and provides habitat and food for a huge chain of marine life. Kina often overpopulate areas when their main predators, snapper and crayfish, are overfished. Photo: Roger Grace

The overfishing that began with commercial fishing was sustained by recreational fishers who came in greater numbers with more sophisticated fishing boats and gear. Fish size, populations and diversity withered. Because great numbers of snapper and crayfish, which eat kina, had been taken, kina populations exploded and have grazed seaweed forests down to rock. Vast areas of kina barrens remain.

The evidence is clear. Dr Grace’s 2007 research along the Mimiwhangata coast, between Mōkau and Whananaki, revealed 1.74 legal-sized crayfish per hectare, compared with 800 per hectare at the protected area at Tawharanui.

“Today, when people find a place with lots of fish they go back there again tomorrow,” Uncle Puke says. “My Dad always said, ‘Every big snapper you catch is a million little ones that won’t be born.’ I suppose he was right.”

Eight years ago, Ngātiwai rangatira Houpeke Piripi (son of the last Ngātiwai paramount chief Morore Piripi), responded by declaring that marine protection was to be pursued by hapū in the district. “I myself feel that there should be a ban or a rāhui tapu placed for at least 20 to 25 years, to allow the seaweed to regenerate so the rare fish, crayfish etc will return…”

Since that day, the road has been rocky. For five years, hapū members and DOC worked through the unwieldy requirements of the 1971 Marine Reserves Act. Boundaries were outlined and public submissions sought as part of a marine reserve proposal in 2004.

Around the same time, the Labour coalition Government put all marine reserve proposals on hold

– including the one for Mimiwhangata – in favour of developing marine protected areas in each region. This process itself has now been suspended in most of New Zealand, including Northland.

As a result, Ngātiwai saw their Treaty partner walk away without explanation. This left all those involved in the process extremely frustrated and disillusioned.

In the meantime, hapū members approached Forest & Bird to get protection for Mimiwhangata moving down a different track that provided for hapū co-governance of the proposed marine reserve area.

I started diving around five years old,“ says Uncle Puke, who has been snorkelling around Mimiwhangata for more than 60 years. “I went to Whāngārei to learn scuba diving in 1957. It opened up a whole new world altogether, Mimiwhangata was an awesome place. The first Spanish lobster I saw was out there. You’d always come across a school of huge snapper and kingfish. Now and then you’d run into a school of dolphins and of course the odd orca. I disappeared quickly when I saw them under the water. I came face to face with hammerheads out there.“

Crayfish. Credit: Shaun Nelson

In the late 1960s, Uncle Puke spotted a 50-pound packhorse crayfish. “I was just swimming over a channel and saw these huge horns sticking out of the seaweed. They were so huge my hands wouldn’t fit around them. I put my jute bag over the top of it and it flapped and swam up to the boat.

“When I first started to fish out there we got red and blue moki. The blue moki is very, very scarce out there now but there’s still muttonbird on the islands, oi [grey-faced petrels] and diving petrels on Rimariki.”

Charles Going of te Whanau Whero from Whananaki has dived at Mimiwhangata all his life. “Literally hundreds of people are diving up there now. There needs to be reserves dotted right up the north saving things for everyone, for the future.”

Deep water sponge gardens. Photo Roger Grace

Uncle Puke says that if we don’t act now, sea life will be “lost and forgotten like the moa. People won’t know what was there before.”

“Since we’ve been discussing the issue of marine reserves it’s made me realise how important it is to manage the resources out there, instead of just thinking about your puku all the time. I like what’s being presented now in that it would help re-establish fish stocks in the area and provide employment for the community. For me that’s really awesome.”

Charles Going points out that a rāhui tapu won’t necessarily create a lot of jobs “but the key thing is the educational side. We want to put a research centre out there similar to what is at Goat Island, working with the university.”

Community leader Carmen Hetaraka says young people are working towards skipper licences and dive qualifications. “We have trained dive instructors for the Tawhiti Rahi /Poor Knights and Motukökako, the Hole in the Rock. We don’t want them out there just taking. There are other opportunities for people with those skills, and developing their kaitiakitanga as part of ecotourism. We see the rāhui tapu being a foundation for economic, education and employment sustainability.”

When life beneath the waves rebounds at Mimiwhangata, it is likely to be more diverse than around Goat Island near Leigh. The area is licked by subtropical currents that support species rarely found on the mainland coast, including foxfish, combfish and tropical surgeonfish.

Along with the bounceback of crayfish and snapper, it is hoped rare species – such as ivory coral, red-lined bubble shell, callianassid shrimp, spotted black grouper, sharpnosed puffer and sabretooth blenny – will become more common.

Reefs stretching four kilometres offshore east of Rimariki Island from Mimiwhangata appear rich with gorgonian fan, soft and black corals and many different fish species. People will be able to see some of New Zealand’s subtropical wonders from the shore with their masks and snorkels. Mimiwhangata is also one of the closest parts of the mainland to the Poor Knights Islands Marine Reserve.

A version of this story first appeared in the February 2011 issue of Forest & Bird Magazine.

MIMIWHANGATA UPDATE 2021

Plans for marine protections around Mimiwhangata have been let down by various Governments for around twenty years. Kaumātua have passed on and so has the baton for having the dream fulfilled. Ngatiwai kaumatua, Puke Haika (interviewed for the story above) has now unfortunately passed away.

Currently Forest & Bird is working together with Ngāti Kuta, Te Uri o Hikihiki, and Bay of Islands Maritime Park in a court challenge based on the ground-breaking precedents set by the Motiti case in the Bay of Plenty to use the RMA to protect sea life.

It’s a David and Goliath battle with those who are fighting for protection pitted against wealthy fishing interests. The ongoing battle is now in the Environment Court.